Katya Sivers - Image Laundering. Warfare As Backdrop

Image Laundering: Warfare As Backdrop

Katya Sivers

Fig. 1. Screenshot from the Vremya program, Channel One, broadcast on March 14, 2022. Fig. 2. The screenshot as published on 93.ru, an online media platform based in Krasnodar, on October 4, 2023, with the words “No war. Stop the war. They are lying to you here. Russians against war” pixelate (https://93.ru/text/incidents/2023/10/04/72774863/)

On 14 March 2022, three weeks after the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Russian Channel One employee Marina Ovsyannikova walked in front of the cameras during the live evening news broadcast of Vremya programme, holding a poster with the slogan “No war. Stop the war. Don’t believe the propaganda. They are lying to you here. Russians against war.” Her gesture mirrored that of a hostage, but instead of a dated newspaper, the live broadcast itself became her alibi, serving as an unambiguous timestamp. Positioned between the anchor and the backdrop, she ruptured the seamless image that the audience had been conditioned to consume.

Ovsyannikova’s five-second act, brief as it was, catalysed an immediate tightening of security protocols: live broadcasts were now subject to a mandatory one-minute delay. This adjustment marked the shift to a sanitised, risk-free presentation of the war, transforming it into a sterilised spectacle, much like an OnlyFans platform for viewers seeking safe gratification: "War, when it has been turned into information, ceases to be a realistic war and becomes a virtual war" (Baudrillard, p. 41).

The cynical and instrumental use of media has been fully appropriated by Russian state television channels, turning the war into a carefully curated spectacle. Fabricated backdrops, often digitally constructed, stand in for the reality of the battlefield, with news anchors reading scripts against these artificial settings. Even live segments from war zones are curated to exclude the human costs of war – refugees, suffering, death – while presenting an image of military might that is sleek, polished, and distant. The broadcast unfolds as a performance, where tanks, airplanes, and missiles are reduced to the status of graphic symbols, digital collages, and 3D renderings, as if they are part of an abstract, sanitised narrative. The hyper-saturated, impersonal nature of these representations transforms the war into an event devoid of empathy or human consequence, happening in a realm far removed from the viewer’s immediate reality.

This media spectacle is not a new development. It has historical antecedents in Russia’s cinematic and media history. One of the most well-known fabrications, Sergei Eisenstein’s October, for example, reimagined the Revolution of 1917 a decade after it had passed. Commissioned by the October Jubilee Committee, the film became one of the Soviet Union’s most ambitious cinematic endeavors, utilising unprecedented resources, including control over an entire city. Eisenstein’s montage techniques – combining “montage of attractions” to elicit emotional reactions with “intellectual montage” to provoke deeper associations – produced a fabricated narrative of revolution. But even this idealised version was subject to censorship: Stalin demanded the removal of all scenes featuring Trotsky just before the film’s premiere.

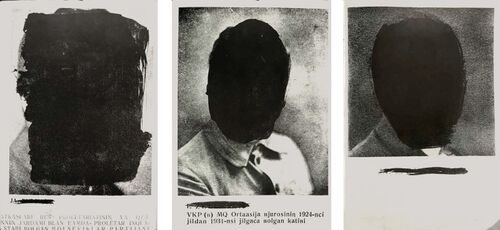

The methods that proved so successful in the early days of Soviet Russia were further exploited by the state with historical photographs. Those who fell out of favor with Stalin were erased, their figures scrubbed from the visual record one by one, while the faces of the “enemies of the people” were obscured with black marks (King 1997). This practice persisted for decades, as the image – now a malleable surface – became a tool for the state’s narrative control, turning even death into a strategic intervention in the visual archive. With the evolution of media technologies, the dynamic between observer and observed has undergone a profound shift. In response, critical artistic interventions have surfaced, where individuals actively obscure their faces as a tactical resistance against surveillance and the pervasive reach of power structures.

Fig. 3. Obscured portraits from “10 Years of Uzbekistan”, an album published in 1934 (Campbell and King)

Today, we witness an accelerated shift in this fabrication of reality. During an October 2024 broadcast, Margarita Simonyan, editor-in-chief of Russia Today (RT), unveiled a startling revelation: RT has abandoned human image editors, entrusting artificial intelligence to curate or create visuals. Moreover, many of the channel’s news anchors are no longer human. These AI-generated figures, complete with hyper-realistic voices, appearances, and carefully calibrated personas, epitomize the merger of technological sophistication with narrative control.

Yet, the most convincing manipulations may still emerge from minimally altered footage of real anchors rather than entirely synthetic creations. This underscores a chilling development: the seamless mutability of digital imagery, stripped of detectable artifacts. Within the forensic community, this process is termed image laundering, where real visuals are transformed into synthetic counterparts, their original traces meticulously erased (Mandelli, Bestagini and Tubaro). But image laundering is not merely a technical phenomenon; it operates as a larger mechanism of obfuscation, an algorithmic sleight of hand that hides reality in plain sight. Details are not just altered – they are erased, rewritten, and multiplied, leaving us with an unprecedented sense of disorientation.

Such disorientation profoundly disrupts relationships between participants in visual – and therefore political – communication, what Ariella Azoulay terms the civil contract of photography. She describes an image as a multifaceted political practice, and its civil contract as a “hypothetical, imagined arrangement regulating relations within a virtual political community” (Azoulay, p. 23). Yet today, this contract has become more complex. Intricate dynamics now unfold not only between viewers and image producers but also within the very strata of the image itself.

The background – both visual and informational – recalls Arjun Appadurai’s notion of colonial photographic backdrops as instruments for experimenting with “visual modernity”. Once passive yet pivotal, such backdrops now operate as silent agents of visual storytelling, functioning as “symptoms of power relations” (Anikina, p. 276). In the context of Russia’s brutal military conflict, society seems to have become accustomed to living against a backdrop of a distant war, unfolding elsewhere. This learned indifference is fueled by image laundering: a process of meticulous fabrication where the layers of war imagery and the loci of attention are carefully curated and polished.

“[War] is beholden not to have an objective but to prove its very existence” (Baudrillard, p. 32), and yet – one of its purposes now seems to conceal its existence entirely, despite the millions of devices documenting it. State power enforces emotional and psychological demobilization through a new societal contract – one that is, in part, a revised contract of photography in this new type of cyberwarfare (Dyer-Witheford and Matviyenko), situated within the framework of “a world imagined and engineered during the Cold War” (Beck and Bishop, p. 24).

Anikina, A. (2023) ‘Things in the Background: Video Conferencing and the Labor of Being Seen’, in A. Volmar, O. Moskatova and J. Distelmeyer, eds. Video Conferencing: Infrastructures, Practices, Aesthetics. (Digital Society) Columbia University Press, pp. 275–292.

Appadurai, A. (1997) ‘The Colonial Backdrop’, Afterimage, vol. 24 (5), pp. 4–7.

Azoulay, A. (2008) The Civil Contract of Photography. New York: Zone Books.

Baudrillard, J. (1995) The Gulf War did not take Place. Trans. by P. Patton. Indiana University Press.

Beck, J. and R. Bishop, eds. (2016) Cold War Legacies: Systems, Theory, Aesthetics. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Campbell, K. and D. King (1994) Ten Years of Uzbekistan: A Commemoration. London: Ken Campbell.

Dyer-Witheford, N. and S. Matviyenko (2019) Cyberwar and Revolution: Digital Subterfuge in Global Capitalism. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

King, D. (1997) The Commissar Vanishes: The Falsification of Photographs and Art in Stalin's Russia. New York: Metropolitan Books.

Mandelli, S. and P. Bestagini, S. Tubaro (2024) ‘When Synthetic Traces Hide Real Content: Analysis of Stable Diffusion Image Laundering’, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2407.10736.

Parikka, J. (2023) Operational Images: From the Visual to the Invisual. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

“Симоньян заявила о замене ведущих RT созданными ИИ аватарами.” (2024). Gazeta.ru. October 29. Accessed January 6, 2025. https://www.gazeta.ru/tech/news/2024/10/29/24263911.shtml.

Comments

here is the comment