Katya Sivers - Image Laundering. Warfare As Backdrop

Image Laundering: A Backdrop

Katya Sivers

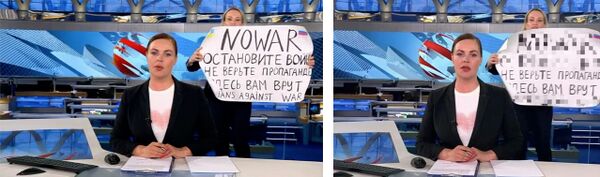

On 14 March 2022, three weeks after the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Russian Channel One employee Marina Ovsyannikova walked in front of the cameras during the live evening news broadcast of Vremya programme, holding a poster with the slogan “No war. Stop the war. Don’t believe the propaganda. They are lying to you here. Russians against war.” Positioned between the anchor and the backdrop, she ruptured the seamless image that the audience had been conditioned to consume. Ovsyannikova’s five-second act catalysed an immediate tightening of security protocols: live broadcasts were now subject to a mandatory one-minute delay.

The cynical and instrumental use of media has been fully appropriated by Russian state television channels, turning the war into a carefully curated performance. Fabricated backdrops, often digitally constructed, stand in for the reality of the battlefield. Even live war-zone segments are curated to obscure human suffering, while military power appears sleek, polished, and distant.

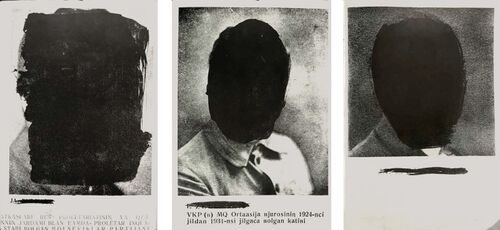

Methods of visual censorship have a long history, particularly in Soviet Russia. For decades, images were altered for political purposes, erasing purged figures from history. One by one, their traces were scrubbed from the visual record, while the faces of “enemies of the people” were obscured with black marks[1].

The image – now a malleable surface – became a tool for the state’s narrative control. With evolving media technologies, we witness an accelerated shift in this fabrication of reality. In an October 2024 broadcast, Margarita Simonyan, editor-in-chief of Russia Today (RT), revealed that RT had abandoned human image editors, and many anchors were now AI-generated figures[2] with hyper-realistic voices and personas, embodying the fusion of technology and narrative control.

Yet, the most convincing manipulations emerge from minimally altered footage rather than entirely synthetic creations. Within the forensic community, this process is termed image laundering[3]. Details of the real visuals are not just altered – they are erased, rewritten, and multiplied, leaving us with an unprecedented sense of disorientation. It profoundly disrupts relationships between participants in visual – and therefore political – communication, what Ariella Azoulay termed the civil contract of photography, a “hypothetical, imagined arrangement regulating relations within a virtual political community”[4]. Today, this contract has grown more complex. Intricate dynamics now unfold not only between viewers and image producers but also involve the state and the very strata of the image itself.

The background – both visual and informational – recalls Arjun Appadurai’s notion of colonial photographic backdrops[5]. Once passive yet pivotal, such backdrops now operate as silent agents of visual storytelling and “symptoms of power relations”[6]. In the context of Russia’s brutal military conflict, society seems to have become accustomed to living against a backdrop of a distant war. “[War] is beholden not to have an objective but to prove its very existence”[7], and yet one of its purposes now seems to conceal its existence entirely, despite the millions of devices documenting it. The politics of disorientation now manifests through an anesthetic civil contract – a revised contract of photography in this new cyberwarfare[8], framed by “a world imagined and engineered during the Cold War”[9].

- ↑ Campbell, Ken, and David King. Ten Years of Uzbekistan: A Commemoration. Ken Campbell, 1994.

- ↑ “Симоньян заявила о замене ведущих RT созданными ИИ аватарами.” Gazeta.ru, 29 Oct. 2024, www.gazeta.ru/tech/news/2024/10/29/24263911.shtml. Accessed 6 Jan. 2025.

- ↑ Mandelli, Stefano, et al. “When Synthetic Traces Hide Real Content: Analysis of Stable Diffusion Image Laundering.” arXiv, 2024, doi:10.48550/arXiv.2407.10736.

- ↑ Azoulay, Ariella. The Civil Contract of Photography. Zone Books, 2008, p. 24.

- ↑ Appadurai, Arjun. "The Colonial Backdrop." Afterimage, vol. 24, no. 5, 1997, pp. 4–7.

- ↑ Anikina, Alexandra. “Things in the Background: Video Conferencing and the Labor of Being Seen.” Video Conferencing: Infrastructures, Practices, Aesthetics, edited by Axel Volmar, Olga Moskatova, and Jan Distelmeyer, Columbia University Press, 2023, pp. 275–292.

- ↑ Baudrillard, Jean. The Gulf War Did Not Take Place. Translated by Paul Patton, Indiana University Press, 1995, p. 32.

- ↑ Dyer-Witheford, Nick, and Svitlana Matviyenko. Cyberwar and Revolution: Digital Subterfuge in Global Capitalism. University of Minnesota Press, 2019.

- ↑ Beck, John, and Ryan Bishop, editors. Cold War Legacies: Systems, Theory, Aesthetics. Edinburgh University Press, 2016.