PrintTest

Contents

- 1 Editorial: Everything is a matter of distance

- 2 Liminal Data Lives: Aestheticising Trans (In)visibility as Algorithmic Distance

- 3 Choreographing Proximity

- 4 Image Laundering: A Backdrop

- 5 Ready Under Construction

- 6 Dead Glitch (Higher, Faster, Stronger)

- 7 Architecture’s distant images

- 8 Fused Horizons: Narrating Pain, Toxicity and Unavoidable Intimacy in the Anthropocene'

- 9 Folded Distances: Techno-Rhythm and Networked Aesthetics

- 10 Induction of Sonic Distance

- 11 Planetary Messengers

- 12 Perplexity — surveilling through surprise

- 13 The Virtual Viewer: image aesthetic assessment and digitized museum art collections

Editorial: Everything is a matter of distance

Christian Ulrik Andersen, Jussi Parikka, Magdalena Tyżlik-Carver, Søren Pold, Pablo Velasco

The Uruguayan poet Cristina Peri Rossi painfully states that, in love as in boxing, everything is a matter of distance.[1] The elliptic, gelatinous relationship between proximity and distance is the central dynamic for the publication and the research workshop behind, organised by DARC/Digital Aesthetics Research Center (Aarhus University) in collaboration with transmediale festival for art and digital culture, Berlin, with participation of a number of PhD and/or artist researchers whose works and thoughts on the 2025 festival theme are now presented here.[2]

A recurrent focus is how space is produced and manipulated in current techno-culture. Proximity is managed through techniques of approximation, of statistical modes of patterning identities, collectivities, and affective modes of attachment to corporate infrastructure. Distance is the usual preferred term for critical vocabularies, but we are always already immersed in such approximations as we are involved, addressed, captured in platforms and other interfaces of affective persuasion. We ask, what then are the best ways critical digital culture research can do in manoeuvring this situation from platforms to infrastructures, from interface to aesthetics, from love to boxing?

The texts in this issue shift across different media - from sound to software, visual cultures to performance. The authors mobilize their knowledge in how bodies move, how cities move, how bodies are captured in algorithmic technologies, and what is not captured in the dynamics of near-distant-remote modes of sensing and modeling. All this implies different scales of reworking our brief: proximity is not necessarily "near" in the traditional sense (but it can be); remoteness is not necessarily only "distant", and questions of other scales of algorithmic politics have to take into account the logistics of approximation, i.e. the statistical basis that is evident for example in machine learning technologies, including their potential modes of violence. A violence that is both geo-political, takes place in systemic exclusions of people, and generative forces activated by near or far relations that pull in human, nonhuman and more-than-human bodies into datasets.

The publication functions as workshop 'proceedings'. Here, though, the word is used as a verb and an action; it interrogates how proximity and distance unfold in the production of academic writing, for instance the idea peer review, or the conventions of formats and formatting, or the use of particular software for text processing or print. To proceed with - a continuous action that unfolds in multiple ways, with multiple methods, across a shared space of inquiry, pulling things, concepts and bodies into and out of relations that can be processed or (mis)understood, or explained, or followed. The publication is the result of a collective action and reflection on the contributions to the workshop. Prior to the workshop, participants circulated and commented essays of 1,000 words. Essays have been published, edited and commented on a shared wiki (using MediaWiki software), discussed (and reduced) at a workshop, and published using web-to-print techniques that build on the JavaScript library Paged.js[3] and the works of an extended community network.[4] In the same mode as previous editions of the Peer-Reviewed Newspaper [5], this one is also a proceeding experiment with collective making and publishing. Following the workshop, the contributions will be elaborated further for publication in A Peer-Reviewed Journal About [6]_

- ↑ Peri Rossi, Cristina. Otra vez eros. Lumen, 1994.

- ↑ This publication is edited by all participants in the workshop: Daria Iuriichuk, Christoffer Koch Andersen, Maya Erin Masuda, Magda Tyżlik-Carver, Sami Itavuori, Paul V. Schmidt, Ruben van de Ven, Pablo Velasco, Matīss Groskaufmanis, Kola Heyward-Rotimi, Maja Funke, Jussi Parikka, Megan Phipps, Katya Sivers, Nico Daleman, Søren Pold, Nicolas Malevé and Christian Ulrik Andersen

- ↑ https://pagedjs.org/

- ↑ https://servpub.net/

- ↑ https://darc.au.dk/publications/peer-reviewed-newspaper

- ↑ https://aprja.net/

Liminal Data Lives: Aestheticising Trans (In)visibility as Algorithmic Distance

Christoffer Koch Andersen

1. Algorithms >< Transness

Algorithms are presumed to exponentially enhance our lives, but for trans people, algorithmic spaces are violent, and at worst, deathly. Behind the veil of neoliberal techno-optimism, algorithms perpetuate colonial and cisnormative violence that anchor a binary default, where the only possible ‘human’ becomes the white cisgender human - forcing transness out of existence from not fitting the codes making up the valorisation of human life[1][2][3][4][5].

How do we carve out liminal spaces of distance in proximity to, but away from this algorithmic gaze of death? I propose conceptualising the aesthetics of trans lives as uncodeable and as liminal data lives to establish a disruptive strategy of algorithmic distance. How might this uncodeability allow us to consider (im)possible ways of living and distance as resistance?

2. Trans Flesh, Coded Death: Algorithmic Valorisation of Binary Life

Algorithms classify humans into categories embodied by “the bodies that do the interpreting and reacting to the information they provide."[6] . Transness—with its infiniteness, messiness and mutability—works against the algorithmic operations and their binary definiteness, fixedness, and immutability, which renders trans people either hypervisible as a deviance or invisible and erased. This imposes a violent gendering of the human in accordance with colonial cisnormative rules of classification as the distinction of who should live and who must die by “performatively enacting themselves/ourselves as being human, in the genre specific terms of each such codes’ positive/negative system of meanings”[7].

"As someone exploring queer understandings of more-than-human kinship, I found your text deeply resonant with my own interests. This passage, in particular, struck me as incredibly powerful: "In relation to bodies, transness—with its infiniteness, messiness, and mutability—works against the operational principle of algorithms and their binary definiteness, fixedness, and immutability, which renders trans people either hypervisible as a deviance or invisible and erased." Instead of framing these technologies as simply failing to capture trans identities, how might we interpret this act of failure—and the inherent partiality it reveals—as central to our witnessing?" [Maya]

Trans people exist in a liminal space; as codeable by being hypervisible in deviating from binary code, which positions trans people as targets for violence through failure to conform to the necropolitical algorithmic order of life and death; and as uncodeable as algorithms cannot comprehend transness, but computes transness to not exist in the first place. These affects of ‘improper life’ stick to transness from its aberrations from binary structures, which strip the trans body of its human possibility as a coded death.

"I really appreciate how you rethink the aesthetics of trans lives as an entrypoint to examine algorithmic violence. That seems a very powerful take. What particularly stood out for me as central is how "transness is fundamentally uncodeable." [Ruben]

3. Aestheticising Transness as Algorithmic Distance

Utilising the aesthetics of transness to elucidate algorithms involve “sensing – the capacity to register or to be affected, and sense-making – the capacity for such sensing to become knowledge”[8], wherein trans bodies “offer fleshly blueprints for the unbuilding of binary understandings”[9]. This operationalisation opens trans algorithmic experiences and translate these into refusal of algorithmic systems. Trans people inhabit a liminal yet powerful space of sensing the algorithmic between the visible/invisible, codeable/uncodeable and liveable/unliveable, where trans ‘error’ in contrast to cisnormative data lives encode a distance that encourages tactics of refusal for algorithmic infrastructures to be reimagined; a space where algorithmic infrastructures are troubled, distorted, and glitched from how transness exists in/against the code.

"You describe for us the relation between algorithms and trans bodies as a liminal distance that starts at the point of rejecting or ommitting transness from available/possible categories that are necessary for binary logic that define algorithms. This is the trap that trans people find themselves in, or as you say, they inhabit this space and in this praxis of living they 'sense' and 'refuse', trouble, delay, distort and glitch algorithmic infrastructures. What kind of relation do these errors generate between bodies and algorithms?" [Magda]

Transness embodies an ‘in-betweenness’ that infiltrates binary code, renders it futile as universal truth and effectuates distance to the reductionist algorithmic readability of humanness towards redefining the means of be(com)ing human. By not fitting into binary code, transness strategically activates a fugitive resistance against algorithmic violence from embodied investment in failure; cutting over, falling through and obscuring flows of code towards liberatory, autonomous and plural algorithmic futures.

- ↑ Amaro, Ramon. The Black Technical Object: On Machine Learning and the Aspiration of Black Being. Sternberg Press, 2022.

- ↑ Andersen, Christoffer Koch. "Wrapped Up in the Cis-Tem: Trans Liveability in the Age of Algorithmic Violence. Special Issue: Ruptures, Resistance, Reclamation: Global Feminisms in Digital Age." Atlantis: Critical Studies in Gender, Culture & Social Justice. 2025, Forthcoming. Preprint: https://osf.io/preprints/socarxiv/tracm

- ↑ Costanza-Chock, Sasha. "Design justice, AI, and escape from the matrix of domination." Journal of Design and Science 3.5 (2018): 1-14. https://doi.org/10.21428/96c8d426

- ↑ Shah, Nishant. "I spy, with my little AI: How queer bodies are made dirty for digital technologies to claim cleanness." Queer Reflections on AI. Routledge (2023): 57-72.

- ↑ Scheuerman, Morgan Klaus, Madeleine Pape, and Alex Hanna. "Auto-essentialization: Gender in automated facial analysis as extended colonial project." Big Data & Society 8.2 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1177/20539517211053712

- ↑ Wilcox, Lauren. "Embodying algorithmic war: Gender, race, and the posthuman in drone warfare." Security dialogue 48.1 (2017, 17): 11-28. https://doi.org/10.1177/0967010616657947

- ↑ Wynter, Sylvia. "Human being as noun? Or being human as praxis? Towards the Autopoetic Turn/Overturn: A Manifesto." (2007, 30). https://bcrw.barnard.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/Wynter_TheAutopoeticTurn.pdf

- ↑ Fuller, Matthew, and Eyal Weizman. Investigative aesthetics: Conflicts and commons in the politics of truth. Verso Books, 2021. (33).

- ↑ Halberstam, Jack. "Unbuilding Gender". Places Journal. (2018). https://doi.org/10.22269/181003

Choreographing Proximity

Daria Iuriichuk

Imagine coming across a girl in your Instagram feed: her face very close to the camera, she’s maintaining eye contact, and smiling kindly, so that you can notice her cute cheek dimples and feel hypnotized. She creates a sense of presence that is almost uncomfortably intimate, leveraging the illusion of physical proximity to connect with thousands of followers. On platforms like Instagram or OnlyFans, these techniques of approximation become a conspicuous tool for creating intimacy, often blurring boundaries between public performance and private connection. However, there is still a distance.

In response to Olga Goriunova’s political call to confront the erasure of distance between digital subjects and “the humans, entities, and processes they are connected to,” which are “constructed not only to sell products but also to imprison, medically treat, or discriminate against individuals”[1], I propose focusing on the ways proximity can be (de)constructed. To explore this, I suggest using choreographic approaches as a conceptual framework for engaging with the critical and creative potentialities of algorithmic thinking. Platforms and algorithms, much like choreographic systems, structure interactions by managing attention, (de)constructing affect and production of body taxonomies. Emerged as a Louis’ XIV court practice of political control "to regulate — and even synchronize — the bodies and behaviours of his courtiers"[2], choreography, a tool of writing down movement, could be observed as a ‘technique designed to capture actions’ [3], a medium that abstracts movement into data, enabling further technical or creative processes. By abstracting bodily movement into data, choreography transforms it into systems of control and knowledge production, shaping behaviour by training bodies to perform socially acceptable identities. Similarly, digital data aggregated today to mobilize bodies within a fluid logic of surveillance capitalism, where movement itself is harnessed for commodification. In this sense, choreography and algorithms both function as technologies of subject formation, conditioning our behaviours and interactions in increasingly automated and commodified ways.

Within contemporary dance, various strategies have emerged to critically reframe the score, construct affect, and make techniques of approximation visible and manipulable. In dealing with choreography, dance brings the body into play, challenging the disembodied narratives of digital intimacy. In Candela Capitán’s dance piece SOLAS [4]approximation techniques are explored from a detached, bird's-eye perspective. On stage, five webcam performers in pink tight suits perform their own erotic solos in front of their laptops, simultaneously broadcasting live with an audience via the Chaturbate platform. Capitán reveals the gap between the digital subject and the labour that sustains it, making this distance strikingly palpable. By exposing the fractured connections and isolating conditions of digital performance, SOLAS lays bare the mechanisms through which intimacy is manufactured, commodified, and consumed in virtual spaces. Candela’s critical gesture is achieved by revealing living bodies behind digital subjects. By foregrounding the performers’ corporeal presence, it insists on the presence of the body as essential for critique in the age of algorithmic mediation.

- ↑ Goriunova, Olga. “The Digital Subject: People as Data as Persons.” Theory, Culture and Society 36 (6), 2019, pp. 125–145.

- ↑ Mcclary, Susan. “Unruly Passions and Courtly Dances: Technologies of the Body in Baroque Music,” From the royal to the Republican body: Incorporating the Political in Seventeenth- and Eighteenth-Century France, edited by Sara E. Melzer and Kathryn Norberg, University of California Press, 2023, pp. 85–112.

- ↑ Lepecki, André. “Choreography and Pornography.” Post-dance, edited by Danjel Andersson, Mette Edvardsen, Mårten Spångberg, MDT, 2017, pp. 67–82.

- ↑ Capitán, Candela. "SOLAS." YouTube, uploaded by CANDELA CAPITÁN, 25 April 2024 , https://youtu.be/TQlQXZGt70k?si=K-97EdxqpBvOuNui.

Image Laundering: A Backdrop

Katya Sivers

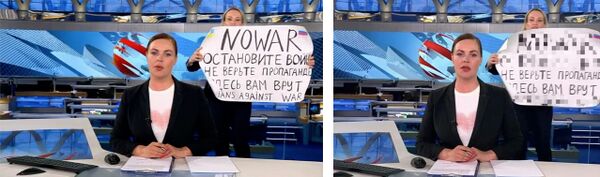

On 14 March 2022, three weeks after the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Russian Channel One employee Marina Ovsyannikova walked in front of the cameras during the live evening news broadcast of Vremya programme, holding a poster with the slogan “No war. Stop the war. Don’t believe the propaganda. They are lying to you here. Russians against war.” Positioned between the anchor and the backdrop, she ruptured the seamless image that the audience had been conditioned to consume. Ovsyannikova’s five-second act catalysed an immediate tightening of security protocols: live broadcasts were now subject to a mandatory one-minute delay.

The cynical and instrumental use of media has been fully appropriated by Russian state television channels, turning the war into a carefully curated performance. Fabricated backdrops, often digitally constructed, stand in for the reality of the battlefield. Even live war-zone segments are curated to obscure human suffering, while military power appears sleek, polished, and distant.

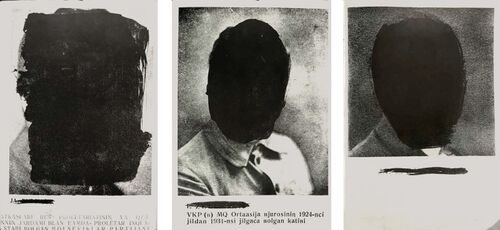

Methods of visual censorship have a long history, particularly in Soviet Russia. For decades, images were altered for political purposes, erasing purged figures from history. One by one, their traces were scrubbed from the visual record, while the faces of “enemies of the people” were obscured with black marks[1].

The image – now a malleable surface – became a tool for the state’s narrative control. With evolving media technologies, we witness an accelerated shift in this fabrication of reality. In an October 2024 broadcast, Margarita Simonyan, editor-in-chief of Russia Today (RT), revealed that RT had abandoned human image editors, and many anchors were now AI-generated figures[2] with hyper-realistic voices and personas, embodying the fusion of technology and narrative control.

Yet, the most convincing manipulations emerge from minimally altered footage rather than entirely synthetic creations. Within the forensic community, this process is termed image laundering[3]. Details of the real visuals are not just altered – they are erased, rewritten, and multiplied, leaving us with an unprecedented sense of disorientation. It profoundly disrupts relationships between participants in visual – and therefore political – communication, what Ariella Azoulay termed the civil contract of photography, a “hypothetical, imagined arrangement regulating relations within a virtual political community”[4]. Today, this contract has grown more complex. Intricate dynamics now unfold not only between viewers and image producers but also involve the state and the very strata of the image itself.

The background – both visual and informational – recalls Arjun Appadurai’s notion of colonial photographic backdrops[5]. Once passive yet pivotal, such backdrops now operate as silent agents of visual storytelling and “symptoms of power relations”[6]. In the context of Russia’s brutal military conflict, society seems to have become accustomed to living against a backdrop of a distant war. “[War] is beholden not to have an objective but to prove its very existence”[7], and yet one of its purposes now seems to conceal its existence entirely, despite the millions of devices documenting it. The politics of disorientation now manifests through an anesthetic civil contract – a revised contract of photography in this new cyberwarfare[8], framed by “a world imagined and engineered during the Cold War”[9].

- ↑ Campbell, Ken, and David King. Ten Years of Uzbekistan: A Commemoration. Ken Campbell, 1994.

- ↑ “Симоньян заявила о замене ведущих RT созданными ИИ аватарами.” Gazeta.ru, 29 Oct. 2024, www.gazeta.ru/tech/news/2024/10/29/24263911.shtml. Accessed 6 Jan. 2025.

- ↑ Mandelli, Stefano, et al. “When Synthetic Traces Hide Real Content: Analysis of Stable Diffusion Image Laundering.” arXiv, 2024, doi:10.48550/arXiv.2407.10736.

- ↑ Azoulay, Ariella. The Civil Contract of Photography. Zone Books, 2008, p. 24.

- ↑ Appadurai, Arjun. "The Colonial Backdrop." Afterimage, vol. 24, no. 5, 1997, pp. 4–7.

- ↑ Anikina, Alexandra. “Things in the Background: Video Conferencing and the Labor of Being Seen.” Video Conferencing: Infrastructures, Practices, Aesthetics, edited by Axel Volmar, Olga Moskatova, and Jan Distelmeyer, Columbia University Press, 2023, pp. 275–292.

- ↑ Baudrillard, Jean. The Gulf War Did Not Take Place. Translated by Paul Patton, Indiana University Press, 1995, p. 32.

- ↑ Dyer-Witheford, Nick, and Svitlana Matviyenko. Cyberwar and Revolution: Digital Subterfuge in Global Capitalism. University of Minnesota Press, 2019.

- ↑ Beck, John, and Ryan Bishop, editors. Cold War Legacies: Systems, Theory, Aesthetics. Edinburgh University Press, 2016.

Ready Under Construction

Kola Heyward-Rotimi

“One question we get a lot is when will Eko Atlantic City be ready? Well the answer is: today!”[1] This quote is from the developers of an urban development project in Nigeria. They are constructing a planned city called Eko Atlantic on an artificial island approximately half the size of Manhattan, transforming Lagos’s shoreline. The island, and the city, barely existed fifteen years ago. Today, Eko Atlantic is simultaneously one of the most luxurious places in Nigeria and an active construction site. Emphasis on active: during my visit,[2] there was never a view of the horizon that was clear of tower cranes. Take Eko Pearl Towers as an example, a popular destination. The twin skyscrapers house restaurants, a massive pool, and apartments, all while being surrounded by planes of grassy sand and bulldozers. How does the collapse of distance between the construction site and the completed aspects of the city cohere as one location, one social world?

This cohesion is what I think of as creating seamlessness, bridging the physical gap between what remains incomplete and what has already been built, and making the concept of “incomplete” irrelevant. Luxury living is made possible in Eko Atlantic through creating an aesthetic seamlessness that does not deny the physical environment’s fragmented nature, but perhaps relies on that ragged edge, the mixer trucks and piles of concrete, to contrast the fine dining and photo booths. Eko Atlantic gleams in social media and advertising. Through such lenses, it is “ready.”

The creation of seamlessness in Eko Atlantic and other planned cities like it is the same mechanism that coheres Fanon’s white “settlers’ town” and black “native town” into the bifurcated place of the colony.[3] These urban imaginaries of construction can act as agents of displacement, like Netanyahu’s architectural pitch deck to pave over the cities and lives that Israel burns to the ground in Gaza,[4] and the Thiel-backed “city startup,” Praxis, voicing public excitement over Trump’s threats to invade Greenland, which would secure them the land to construct their “free city” based on “Arthurian myth."[5]

In framing seamlessness in planned cities so that its displacement and violence is centered, instead of its ability to create an affect, it is useful to understand the planned city as a topology of repression. Instead of an aesthetic emerging from the constituent parts, including the people who build, work, and live there, the negative imprint of the land is what truly makes seamlessness. Seamlessness relies on terra nullius logic, suppressing whatever may contradict its claim to the blank slate. These projects function on a collapse of distance between the material, virtual, and psychosocial layers of the city.

- ↑ “When will Eko Atlantic be ready?” YouTube, uploaded by Eko Atlantic, October 23rd 2019, https://youtu.be/kqJ-2KRfJd0?si=-ePHv6h3ubzR1dbU.

- ↑ Thanks to Stanford’s King Center on Global Development for funding this fieldwork.

- ↑ Fanon, Frantz. The Wretched of the Earth. Grove Atlantic, 2007. p. 39.

- ↑ Roche, Daniel Jonas. “Netanyahu unveils regional plan for “free trade zone” with trains to NEOM.” The Architect’s Newspaper, May 21st 2024, https://www.archpaper.com/2024/05/benjamin-netanyahu-unveils-regional-plan-free-trade-zone-rail-service-neom/.

- ↑ @praxisnation. “How to transform Greenland into a technological powerhouse, terraforming experiment, and US strategic asset founded on Arthurian myth.” Twitter/X, January 8th 2025, 6:03pm, https://x.com/praxisnation/status/1877038352412680567.

Responses

"How is the seamlessness translated between project material (decks, renderings, fly-through videos) and the actual materialization of these plans? You mention this in the beginning of your piece, and I think it resonates with my text about architecture's imaging cultures and the gap between the projected and the actual. A rendering of a planned city is not the same as the planned city itself, and the notion of seamless (experience, urbanism, gaze, ...) is represented and made operative in different ways in both of these domains." --Matīss Groskaufmanis

"Would you re-emphazise chaos as a strategy of deconstructing colonial/westernized sobriety of control in architecture and urbanism? Would fiction and world making fantasies still be a tool of creation that you consider (but from the opposite perspective)?" --Maja Funke

Dead Glitch (Higher, Faster, Stronger)

Maja Funke

»Dead Glitch« is a research project and a multimedia body of work that was initiated in view of the global event of the 2024 Olympic and Paralympic Games in Paris. The project places the issue of comprehensive algorithmic video surveillance at the center of attention.

Urban design is updated in the Parisian gaze. What seems to be a streetlamp is no longer a distributor for romantic light, but a surveillance instance in empire green or anthracite. Some five-eyed sentries are special in their materialization of control and freedom may not seem dissuasive but rather belonging (Fig. 1). This is a security enforcement with symbolic aesthetic, in the heritage of the penetrability of the urban space in Louis’ XIV »Ville Lumière«[1]. This light is more often than not interested in non-white bodies and other visible minorities.

Algorithmic Video Surveillance (AVS) consists of the installation and use of software that executes the analysis of videos to detect, identify or classify certain behaviors, situations, objects and people. The various machine-learning-based applications[3] are mainly used by the police in conjunction with surveillance cameras: either for real-time detection of certain suspicious or risky »events« or retrospectively as part of police investigations. Biometric identification allows a person to be recognized in a sample of people on the basis of physical, physiological or behavioral patterns.[4]

While walking Paris in dérive[5], one might sense the onset of normalization of the New Military Urbanism[6]. Counter observation reveals the banalization of a watching city. In the multimedia body of work »Dead Glitch« this walk becomes an investigative performance. In playing with the current legal situation in Paris, the proclaimed zones of AVS are becoming a stage, with the security apparatus documenting the everyday risk-management of the performer and becoming acutely conscious of the resulting instruments of recognition[7] (Fig. 2). The performers journey of becoming data and losing its anonymity and privacy is highlighting these same values a vital for freedom like demonstration, movement and expression.

When video surveillance is not a material apparatus, but a practice[1], there is place to argue for a proximity to social justice[12] and bringing back in mind that historically, antifascist countermovements strenghen in response to a tightening of state security.

»By adding cameras, the idea of the romantic city, the city of the flâneur, has shifted. Contemporary city management seems to have different expectations of what public space is and does. Your artistic strategy to claim CCTV data by using GDPR regulations is a wonderful strategy of resistance. This is a laborious endeavour, both for you and the city, that slows down the cogs of the surveillance machine. It functions as a strong example of what "surveillance as a practice" entails, and how CCTV is so much more than mere technology, but a site of contestation.« – as commented by Ruben van de Ven

»2024 Parisian city surveillance is very effective for me, particularly how you aim to understand what "dataveillance" does in crafting, and controlling, citizens' behavior. Thinking alongside Shannon Mattern (particularly her book The City Is Not a Computer), I'd argue that autonomous systems of surveillance might have changed their distribution of materials, but these systems have been equally present in urban design before the CCTV era.« – as commented by Kola Heyward-Rotimi

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Kammerer, Dietmar: Bilder der Überwachung. Suhrkamp Verlag, 2008.

- ↑ République Française: LOI n° 2023-380 du 19 mai 2023 relative aux jeux Olympiques et Paralympiques de 2024 et portant diverses autres dispositions.

- ↑ Such as Cityvision by Wintics and Briefcam software.

- ↑ https://www.laquadrature.net/vsa/

- ↑ https://situationist.org/periodical/si/issue-2-1958-en/theory-of-the-derive-73

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Graham, Stephen: Cities Under Siege: The New Military Urbanism. Verso, 2010.

- ↑ Boehm, Gottfried: Zwischen Auge und Hand : Bilder als Instrumente der Erkenntnis. In: Mit dem Auge denken : Strategien der Sichtbarmachung in wissenschaftlichen und virtuellen Welten. Zürich, 2001, pp. 43-54.

- ↑ Foucault, Michel: Society Must be Defended: Lectures at the Collège de France 1975-76, Penguin Classics 2020.

- ↑ "Wie die EU mit Künstlicher Intelligenz ihre Grenzen schützen will", Algorithm Watch, ZDF Magazine Royale 24 May, 2025. https://fuckoffai.eu/Accessed November 11, 2024.

- ↑ "Targeted? Killing", Forum InformatikerInnen für Frieden, 29 April, 2024. https://blog.fiff.de/content/files/2024/04/2024_04_29_Stellungnahme-lavender.pdf. Accessed 3 May, 2024 and "‘Lavender’: The AI machine directing Israel’s bombing spree in Gaza", +972 Magazine, 3 April, 2024. https://www.972mag.com/lavender-ai-israeli-army-gaza/ Accessed April 15, 2024.

- ↑ Mulligan, Cathy: Automated Warfare and the Geneva Convention. Netzpolitik, 17 April, 2024. https://netzpolitik.org/2024/artificial-intelligence-automated-warfare-and-the-geneva-convention/?via=nl Accessed 11 November, 2024.

- ↑ "Intelligence artificielle : la France ouvre la voie à la surveillance de masse en Europe", Disclose, 22 January, 2025 https://disclose.ngo/fr/article/intelligence-artificielle-la-france-ouvre-la-voie-a-la-surveillance-de-masse-en-europe. Accessed 22 January, 2025.

Architecture’s distant images

Matīss Groskaufmanis

An image is not a building, and a building is not an image. The shaping of the built environment through planning and construction rests on the separation between representation and operation. A building is a spatial outcome of a mobilization of material resources, labor, and time. It is also a product of both visual and alphanumeric assembly instructions that suggest its appearance and properties. Yet, the ongoing enmeshment of computation and material worlds, or as Wigley (2017) put it—the shift from paper to screen space—suggests that buildings and images do not exist too far apart either.[1] In today’s information-rich environments, not only proteins, microchips, wind turbine blades, cars, but also architecture is increasingly often “twinned” with highly detailed digital replicas that are used in simulations, stress tests, maintenance planning, life cycling analysis and other forms of predictive planning.

Since the advent of networked computing and graphics processing in the 1990s, much of architecture’s imagination was captured by the new formal possibilities (e.g. the practices of Zaha Hadid, Greg Lynn and their contemporaries), but also the intersection between digital and physical environments. One example is the “phygital” version of NYSE trading floor designed by Asympotte (2000), another would be MVRDV’s Metacity/Datatown project (1999) where data is a substance from which cities are made.[2][3] Amidst these explorations, arguably a more consequential development has been the widespread adoption of building information modeling (BIM) protocol, which affords the possibility of collapsing all possible information about a building into a single digital entity. Cardoso-Llach (2017) describes such models as “structured images”, which unlike visual images, function as mechanism where every building part is held together by parametrically defined interdependencies.[4]

As a result, most buildings nowadays are built at least twice—first as a structured image, then as an object. Often, they are built many times more, as they co-evolve over time through feedback loops of information exchange between digital and physical environments, surveys, projections, and simulations. All such forms of the building contain information. While the image version of building information is computed via electronic signals, stored in data structures, operated via software platforms, rendered in polygons, and displayed on grids of illuminated squares, its physical version contains information encoded not as data but as the particular arrangement and properties of physical matter. [5]

A building can be an image, and an image can be a building. While BIM represents the most common form of real-time imaging of the built environment, this logic applies to other domains too, such as landscape and city information modeling, as well as the broader forms digital twinning at scales including the planetary, as exemplified by EU’s initiative to build an operational digital replica of the Earth, called Destination Earth.[6] Yet, tethering more material and finer scales to real-time electronic images remains a challenge, if not an impossibility. Both atomic and subatomic structures of matter function differently from computational concepts like pixels, vectors, meshes, textures, and simulation engines, and interpreting data between them involves approximation, noise and other forms of information loss. This distance between material realities and their twinned replicas remain more than a technical obstacle, but perhaps also suggests possibility of other building cultures to emerge.

✺✺✺

- ↑ Wigley, Mark. “Black Screens: The Architect’s Vision in a Digital Age.” When Is the Digital in Architecture?, edited by Andrew Goodhouse and Canadian Centre for Architecture, Sternberg Press, 2017.

- ↑ Asymptote Architecture. NYSE Virtual Trading Floor. Canadian Centre for Architecture, 2015.

- ↑ Maas, Winy and MVRDV (Firm), editors. Metacity Datatown. MVRDV/010 Publishers, 1999.

- ↑ Cardoso Llach, Daniel. “Architecture and the Structured Image: Software Simulations as Infrastructures for Building Production.” The Active Image, edited by Sabine Ammon and Remei Capdevila-Werning, vol. 28, Springer International Publishing, 2017, pp. 23–52.

- ↑ May, John. “Everything Is Already an Image.” Log, no. 40, 2017, pp. 9–26.

- ↑ European Commission. “Destination Earth.” Destination Earth, https://destination-earth.eu/. Accessed 30 Jan. 2025.

Responses:

"I can't help but read the text in a way that is not just material-centred [...] does „all possible information about a building“ already contains the ones about the living entities inside? Or is the human component the agents role that would be elaborated in a further step?" —Maja Funke"You're definitely onto something with linkage between virtual abstractions and physical constructions, though I'd say there's a lot of cases where digital and physical spaces are coevolving. In some of the cases I'm thinking about, the construction site, its physicality, functions as generative material for the development of digital mirror worlds, which then go on to structure the buildings-to-come at the site. It's a push-and-pull dynamic that makes it hard to put one in front of the other." —Kola Heyward-Rotimi

"I was wondering how this relates to the semiotics of architecture and cities - including the interpretation and construction of architectural discourse + the (un-)readability of architecture and the urban. To what degree, and how, is this different than the idea of the city as semiotic space, which we know from modern cities?" –Søren Pold

Fused Horizons: Narrating Pain, Toxicity and Unavoidable Intimacy in the Anthropocene'

Maya Erin Masuda

We live in an era of bio-molecular politics. Paul B. Preciado, for instance, describes the ways in which pharmaceutical and pornography industries design and regulate bodies and desires as the “pharmacopornographic regime”[1]. While Preciado focuses on the semiotic and biotechnological interventions that shape individual bodies, Michelle Murphy examines the uneven spatio-temporal distribution of chemicals across landscapes, a phenomenon she terms “chemical infrastructure.”[2] Though their approaches differ—one centered on hormonal transformations and the other on environmental degradation—both theories converge in revealing how more-than-human bodies are shaped as socially constructed artifacts of larger biopolitical systems through molecular interventions. Mel Chen conceptualizes this entanglement as “molecular intimacy”[3] , emphasizing the autonomous behavior of toxins as they circulate, merge, and disrupt existing systems of control.

Radioactivity that mutates and transforms bodies serve as a compelling example to the “molecular intimacy”. Therefore as an interface of negotiation of scales, through my creative practice I have explored the many ways in which more-than-human surfaces such as human, animal, or landscape, planetary skin, serves as a witness to the surrounding biopolitical conditions. The Borderer, the work which I presented in 2023, problematizes the unavoidable multispecies intimacy through formulating speculative surfaces of an anonymous land. I trained a generative AI (GAN) model using 2,500 microscopic photographs of skin abnormalities of animals that remained after nuclear catastrophes and 2,500 satellite images of planetary surfaces where historically severe contamination has been experienced. This process generated over 5,000 photographs of grey spectrum between skin and landscape [figure 1.2]. What astounded me the most was how the computational gaze of neural networks—through its pattern recognition capabilities—constructed an alternative skin, perceiving the references with an intimate, almost caressing gaze. The photographs blur the lines between tumors and mountains, producing uncanny surfaces where beauty and toxicity coexist, leaving room for speculation: scales collapsed, revealing how anthropocentric activities alter entire landscapes from a molecular level.

How could we comprehend such uncanny surfaces? Mel Chen might again provide a crucial lens. Chen critiques the stigmatization and exclusion of mutant bodies, particularly their deformities, illnesses, and toxicity, which Chen conceptualizes as “toxic queerness.” [4]Chen’s interpretation of queerness resonates with Heather Davis’s discourse on a future based on non-reproduction[5]. By focusing on the inheritance of spatiotemporal distribution of chemicals, Davis opens a pathway to perceive various non-human entities affected by the anthropocentric activities as “queer kin”[6] of humankind. This reimagination of kinship, untethered from reproduction, allows us to understand ecosystems as networks of circulating molecules and explore the ambivalent intimacy that emerges within these entanglements.

- ↑ Preciado, Paul B. Testo junkie: sex, drugs, and biopolitics in the pharmacopornographic era. 2013

- ↑ Murphy, Michelle. “Chemical infrastructures of the St Clair River.” Routledge eBooks, 2015, pp. 103–15. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315654645-6.

- ↑ Chen, Mel Y. Animacies: biopolitics, racial mattering, and Queer affect. 2012, https://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BB12645740

- ↑ Chen, Mel Y. Animacies: biopolitics, racial mattering, and Queer affect. 2012, https://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BB12645740

- ↑ Davis, Heather. “Plastic matter.” Duke University Press eBooks, 2022, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv29z1hfb

- ↑ Davis, Heather. “Plastic matter.” Duke University Press eBooks, 2022, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv29z1hfb

Folded Distances: Techno-Rhythm and Networked Aesthetics

Megan Phipps

The techno-aesthetic experience of the networked rave is a dialectic of intimacy and distance, a dance of spatial and rhythmic dynamics oscillating between proximity and separation, individuality and collectivity, orientation and disorientation. The foggy dancefloor, saturated with recursive rhythms and stroboscopic flickers, embodies a rhythmic space[1]: a site where collective resonance dissolves rigid spatial boundaries, while reasserting the interplay of center and periphery. Distance is not erased but folded, stretched, and reframed within industrial-mechanical recursive cycles of decentralised visuals, sound, light, and (collective) movement. These recursive oscillations serve as both structuring force and site of disjunction—a deterritorialized zone of molecular motion where identity, agency, and perception are rendered and recalibrated. The techno-aesthetic event, like Germany’s Tekknozoid (Fig. 1) or Dreamscape (Fig. 2), transforms physical space into rhythmic space. The techno surround-sound[2] is both liberating and oppressive: it promises escape from surveillance, capitalist time, and social judgment, while simultaneously demanding submission to its mechanical recursion.

In techno-events, virtual augmentation reconstructs proximity through rhythmic entrainment, transforming collective movement into shared sensory experiences—a distributed intimacy mediated by rhythm and audiovisual affect.[3][4][5][6][7][8][9] Distance simultaneously manifests as resonant intervals—liminal suspensions of flickering beats, fragmented gestures, and remixed imagery. Layered visuals, sonic synchronicities and recursive oscillations evoke a liminal Fold,[10] compressed in density and entangled across time and space. Teetering between proprioception and vertigo, these folded distances exemplify “network anesthesia”,[11] where rhythmic ecstasy and numbing simultaneity converge. This network-disorientation functions as both a “technique of ecstasy” and a numbing simultaneity of nodes, links, and flows that obscure relationalities from the local to the global.

Experimental filmmaker and VJ Peter Rubin captures these dynamics in split-screen panels and rapid rhythmic alternations.[12] His projections, such as Mayday VisionMix 1 (1992) (Fig. 3), anticipated today’s techno-aesthetics: hypermodulated, synthetic visuals traversing a "sea of data"[13]—a corpuscular media-ecological fog[14][15] of networked bombardment. This lineage extends toward contemporary techno-images that float within vast networked assemblages: slippery, sticky,[16][11] "groundless"[17] configurations layered within rendered ambiguity and buffered abstraction.

Rhythm extends beyond the temporal patterns of a techno beat and into pulses[18] of bio-technical systems of internal/external resonance, mediating the interaction between organic and machinic domains[19] through “technoecologies of sensation”[20] of tranductive interaction. Synchronization between organic movement and machinic processes enhances proximity and control, as seen in apps like Google Maps or Strava. These apps, linking to platforms like Spotify, foster distributed intimacies through rhythmic cycles of asynchronous interaction, blurring the lines between physical and virtual, organic and mechanical.

This political-aesthetic shift marks the transformation from linear input/output models to recursive feedback loops, expanding distances and fostering distributed intimacies. Techno-rhythm mediates the entanglement of proximity and distance, reshaping intimacy, communication, and collective experience in networked environments. Recursive feedback loops and algorithmic flows destabilize fixed sensory frameworks, transforming perception and meaning. This shift in the ontology of trance marks a move from bounded cinematic frames to pervasive networked conditions embedded within folded distances.

The question then remains: where, exactly, are these folded distances leading us towards?

- ↑ Lefebvre, Henri. Rhythmanalysis: space, time, and everyday life. New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2017.

- ↑ Turner, Fred. (2013). The Democratic Surround: Multimedia and American Liberalism from World War II to the Psychedelic Sixties. Chicago; London: The University of Chicago Press.

- ↑ Butler, Mark J. Unlocking the Groove: Rhythm, Meter, and Musical Design in Electronic Dance Music. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2006.

- ↑ Gaillot, Michel. Multiple Meaning Techno: An Artistic and Political Laboratory of the Present. Paris: Editions des Voi, 1999.

- ↑ Garcia, Luis-Manuel. “Feeling the Vibe: Sound, Vibration, and Affective Attunement in Electronic Dance Music Scenes.” Ethnomusicology Forum 29 (1), 2020, p. 21-39.

- ↑ Holl. Ute. Cinema, Trance, & Cybernetics. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2017.

- ↑ Reynolds, Simon. Energy Flash: A Journey through Rave Music and Dance Culture. London; Picador: Faber and Faber Incorporated, 1998.

- ↑ St. John, Graham. (2009). Technomad: Global Raving Countercultures. London: Equinox Publishing Ltd.

- ↑ Thorton, Sarah. (1995). Club Cultures: Music, Media and Subcultural Capital. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- ↑ Deleuze, Gilles.The Fold: Leibniz and the Baroque. New York: Continuum, 1988: 2006.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Munster, Anna. An Aesthesia of Networks: Conjunctive Experience in Art and Technology. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2013.

- ↑ Deleuze, Gilles. (1983). Cinema 1: The Movement-Image. Bloomsbury Revelations, 2020.

- ↑ Steyerl, Hito. (2016). “A Sea of Data: Apophenia and Pattern (Mis-)Recognition.” e-flux journal: Issue #72. URL: https://www.e-flux.com/journal/72/60480/a-sea-of-data-apophenia-and-pattern-mis-recognition/

- ↑ Massumi, Brian. Parables for the Virtual: Movement, Affect, Sensation. Durham & London: Duke University Press, 2002, p. 146.

- ↑ Gibson, James J., & Waddell, Dickins. “Homogenous Retinal Stimulation and Visual Perception.” American Journal of Psychology 65, no.2, 1952, p. 263-70.

- ↑ Rushkoff, Douglas. (2010). Media Virus!: Hidden Agendas in Popular Culture. Random House Publishing Group.

- ↑ Gil-Fournier, Abelardo & Parikka, Jussi. Living Surfaces: Images, Plants, and Environments of Media. Cambridge; London: The MIT Press, 2024.

- ↑ Cowan, Michael.Technology’s Pulse: Essays in Rhythm in German Modernism. Institute of Germanic and Romance Studies. London: School of Advanced Study, University London, 2012.

- ↑ Simondon, Gilbert. (1989). Du mode d'existence de objets techniques. Paris: Aubier-Flammarion.

- ↑ Parisi, Luciana. “Technologies of Sensation.” Deleuze|Guattari & Ecology eds. Bernd Herzogenrath, 2009, p. 182-200.

Induction of Sonic Distance

Nico Daleman

Active Noise Cancelling (ANC) headphones present an example of a sonic interface that isolates the user into a preestablished sonic profile. Nevertheless, their digital manipulation of sonic environments constitutes an affront to the perception of sonic distance. Noise reduction algorithms induce a sonic distance, a parallel perception of reality, contingent to the biases imposed by the algorithm. ANC headphones employ a miniature microphone to capture, process and reproduce surrounding soundscapes. The result comprises the “desired signal” (e.g. music, speech) and the environmental information in its negative (denoised) form.

Cécile Malaspina proposes a reconceptualization of noise from a quantitative measure of information in relation to noise to a qualitative measure of sound, where the first measures a relation of probability, while the latter considers an object of perception.[1] As disturbance of transmission, noise is an act of violence and disruption manifested in interruption and disconnection.[2] As a perceptual phenomenon, noise is socially constructed and situated in hierarchies of race, class, age, and gender and is often coded as othered sound.[3] ANC headphones have the potential to reconfigure noise’s socially constructed demarcations as sensorial experiences. Yet, the compulsory modification of quotidian sounds that are perceived as noise becomes itself an act of violence and disruption.

In audio technology, noise manifests as unwanted signals generated within a system, which could appear by means of electromagnetic induction, a changing magnetic field generates an electrical current. Based on this principle, microphones and speakers transduce energy, from acoustic to electrical and vice versa. For Gilbert Simondon, induction is a unidirectional process that generates plausible realities derived from individual observations and totalizing generalizations and therefore cannot content with heterogeneity. Conversely, transduction provides the basis for an explorative form of thought which is not necessarily teleological or linear, and which allows for reconfigurations of new structures without loss or reduction.[4] Listening as an exploratory activity is then a fundamental transductive act: a process of intuition and individuation that “discovers and generates the heard.”[5]

The unidirectional inductive process takes place in the transformation of environmental sound into a re-production of a sonic generalization, implying a loss of information in the listening act. The acoustic outcome is pre-predetermined by the previous observations of the embedded algorithm, and it is therefore contaminated with the implicit biases of its inductive functioning. The creation of a new signal presented as a re-creation of virtual sonic environments invisibilizes not only the medium, but also the content itself, thus creating a perceptual absence[6] an an-aesthesia, a deaf trust in the algorithm’s definition of noise, which is not accessible by the subject’s perception.

The transductive exploration of the listening act itself is violently removed from agency of the listener, interrupting a process of individuation by acoustically isolating and socially alienating the individual. Instead of negating its surroundings by passively masking it acoustic content[7], ANC induce sonic distance not despite their active awareness of its surroundings, but because of it. The strategies through which ANC headphones are marketed, position them in a social dynamic of othering through sonic distancing between the listener and othered profiles of the soundscape's sonic agents. The promise of soothing experience is only archived by the simultaneous imposition of algorithmic mediation, which replaces exploratory listening with synthetic experience, thus alienating the individual from its embodied sensorial experiences.

- ↑ Malaspina, Cécile. An Epistemology of Noise. London: Bloomsbury, 2018. (154).

- ↑ Attali, Jacques. Noise: The Political Economy of Music, Translated by Brian Massumi. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1985. (26).

- ↑ Hagood, Mack. "Quiet comfort: Noise, otherness, and the mobile production of personal space." American Quarterly 63.3 (2011, 574): 573-589.

- ↑ Simondon, Gilbert. Individuation in light of notions of form and information. Translated by Taylor Adkins. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2020. (15).

- ↑ Voegelin, Salomé. Listening to Noise and Silence. Towards a Philosophy of Sound Art. London: Continuum. 2010. (4).

- ↑ Hagood, Mack. Hush: Media and sonic self-control. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2019. (22).

- ↑ Hosokawa, Shuhei. "The walkman effect." Popular music 4 (1984): 165-180.

Planetary Messengers

PV Schmidt

Telegram is all over the place, India is the country with its biggest user-base. The messenger is legally based in the British Virgin Islands, operated from Dubai, and owned by Pavel Durov, a quadruple citizen of Russia, Saint Kitts and Nevis, the United Arab Emirates, and France.

In August 2024, Durov was arrested at an airport in France and held for four days in custody, with the accusation of facilitation and participation in criminal activities through the lack of moderation within Telegram. Out on a €5 million bail, he shortly afterwards harmonized Telegram’s data sharing with authorities worldwide, and cleared with moderators and ‘AI’ a lot of ‘problematic content’ and banned affiliated users.[1]

A lot of social contact today, is preceded, facilitated or followed by chat, voice messages and calls over messengers. Operated on the internet, messengers appear as a technology transcending borders. In theory, we can seamlessly reach everyone with an internet connection through a messenger. A pledge of a sheer infinite reach is already constrained through obvious inequality in accessibility of technological infrastructure, and capped at many points beyond. The barriers originate from state and supranational legislation, over to app store rulings, or to the service's own moderation. The messengers unveil the delicate state of the open internet, as they’re central to contemporary life.

Messengers are developed and operated on said multilayered-platforms, novel jurisdictional configurations emerge.[2] The concept of the ‘planetary’ helps to bring the infrastructure together with the political to think about messengers; technology as inseparable from politics.[3]

The messengers are influenced by major legislation such as China’s Great Firewall. A juridical and technological arrangement enclosing the internet inside the country through the blockage of manifold traffic, and the overseeing of messages. Within the European Union, internet censorship is utilized similarly for websites, used inter alia to “influence political discourse and favour businesses”.[4] A discussed chat control proposal attempts to oblige messengers to make all communications disclosable within Europe.

Some messengers are end-to-end encrypted by default (Whatsapp, Signal, Viber and iMessage), without access to the terminal devices there is no way to inspect the chats. All the others are not encrypted at all (WeChat), or not encrypted by default (Telegram, KakaoTalk, Viber, and Facebook and Instagram messaging)—but can be enabled through additional configuration, usually with the compromise of fewer features.

A planetary account of messengers needs to consider the geographies of developers and operators as well as users within their respective jurisdiction and local realities, including (geo)political dependencies and disparities as well as local and international inequalities. The planetary-discourse often considers technology as a to-be-managed challenge for grand transnational politics.[5]

But as there’s no universal face-off with technology, confronting it needs to always include the potentially suspicious—minorities and unreasonably prosecuted. The Snowden revelations taught us, that mass-surveillance and democracy are hardly reconcilable.[6] With the messenger, personal sovereignty only materialises through strictly private communication by default.[7]

- ↑ Agence France-Presse. ‘Telegram’s Pavel Durov Announces New Crackdown on Illegal Content after Arrest’. The Guardian, 23 Sept. 2024. The Guardian, https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2024/sep/23/telegram-illegal-content-pavel-durov-arrest.

- ↑ Bratton, Benjamin H. The Stack: On Software and Sovereignty. MIT Press, 2015.

- ↑ Hui, Yuk. Machine and Sovereignty: For a Planetary Thinking. University of Minnesota Press, 2024.

- ↑ Ververis, Vasilis, et al. ‘Website Blocking in the European Union: Network Interference from the Perspective of Open Internet’. Policy & Internet, vol. 16, no. 1, Mar. 2024, pp. 121–48. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1002/poi3.367.

- ↑ For working with ‘Planetary’- narratives, there is a lot to learn from the ‘Anthropocene’. (Simon) provides a brilliant overview over the concept’s development in theory. (Bonneuil and Fressoz) offer a detailed account of the Anthropocene’s overall force to depoliticise. Bonneuil, Christophe, and Jean-Baptiste Fressoz. The Shock of the Anthropocene: The Earth, History and Us. Translated by David Fernbach, Paperback edition, Verso, 2017. Simon, Zoltán Boldizsár. ‘The Limits of Anthropocene Narratives’. European Journal of Social Theory, vol. 23, no. 2, May 2020, pp. 184–99. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1177/1368431018799256.

- ↑ Lyon, David. Surveillance After Snowden. Wiley, 2015.

- ↑ Anderson, Ross. Chat Control or Child Protection? 1, arXiv, 2022. DOI.org (Datacite), https://doi.org/10.48550/ARXIV.2210.08958.

Perplexity — surveilling through surprise

Ruben van de Ven

Camera surveillance has become ubiquitous in public space. Its effects are often understood through Foucault’s description of the panopticon[1]. Regardless of whether an observer is present to monitor its subject, the mere idea of being observed keeps people in check. When discussing surveillance in the public space, the self-disciplining implied by the panopticon suggests people would bow their heads and walk the line. However, in practice, most people seem not to care. Even I, a researcher of algorithmic security, shrug about cameras when I routinely cross the train station, only worrying about catching the next train home. Where then does indifference leave us with critique of algorithmic surveillance?

The past years have seen the introduction of algorithmic techniques in observer rooms that are to guide the operator’s eyes by singling out particular behaviours. By examining how these contemporary technologies negotiate deviancy and normality, I propose to rethink the subject under surveillance.

[Pablo] "… I particularly like how your approach questions the role of the "average citizen" in this power relation, beyond the duality of victim and guilt (or indifference, but I would question that this is the right word for our attitude)."

Algorithmic anticipation

In surveillance, the “deviancy” and “anomaly” serve as catch-all categories for any unexpected behaviour. Security practitioners consider noticing such behaviour an art[2][3]. Working through anticipation practitioners relate “almost in a bodily, physical manner with ‘risky’ and ‘at risk’ groups”[4] to mark people as ‘out of place’.

[Maya] "What made me contemplate is, how should we comprehend this ambiguity of gaze? For example, in the feminist theory, gaze is often discussed as a form of objectification (referred to as male gaze) therefore as a harmful one. […] However, "gaze" also entails care, affection, curiosity, or even desire. I wonder what transforms the same gaze from fatal one to care-full one. […] Indifference (the lack of attention or care) could be a powerful weapon to enforce the larger sociopolitical control."

With the introduction of algorithmic deviancy scoring however, the construction of anticipation needs to be reconsidered. A traditional machine learning detector, trained by example, struggles with an open category like deviancy, which collapses heterogenous behaviours — robbery, traffic accidents, etc. — and includes all that is unknown. Moreover, much more footage is available of people going about their business than of "deviant" behaviour. To overcome these limitations, a logical reversal is invoked.

Instead of detecting deviancy, normality is predicted. Trained on “normal” data, a generative model uses past measurements to simulate the present. These nowcasts are then used to assess the likeliness of present movements. This unpredictability score resembles a metric known as perplexity, which has become a prominent error metric for assessing the futures brought forth by generative algorithms — large language models in particular. Applied to surveillance however, it is no longer the algorithm that errs but the human that is deemed unpredictable. As the present is governed through perplexity, the anomalous is no longer considered as the proximity to a predefined ‘risky’ other, but as a measured distance from a simulated normality.

Routines

Perplexity makes apparent how surveillance capitalises on our day-to-day routines. As we travel set paths through streets, train stations and parks, we co-produce the backdrop of normality against which anomalous movement stands out[5] [6]. No longer is there a clear demarcation between those in the panopticon's tower and those in prison cells. While everyone is watched by surveillance, the majority is not targeted. Rather, they are complicit in constituting normality.

Rethinking the relation between normalcy and deviancy opens up new avenues for resistance. As Michel de Certeau[7] reminds us, walking not only affirms and respects, it can also try out and transgress. In the reciprocal relationship between individual and population, “every action … necessarily destroys the whole pattern in whose frame the prediction moves and where it finds its evidence.” [8] Collectively, we can make normality more unpredictable.

[Daria] "Your last paragraph inspired me to imagine forms of unpredictability. This brought to mind Trisha Brown’s experiments [which seem to be inspired by de Certeau]. However, I wonder: do we by 'making normality more unpredictable' allow AI systems to absorb deviance into the framework of the 'normal'?"

- ↑ Foucault, Michel. 1977. Discipline and punish: the birth of the prison. 1st American ed. New York: Pantheon Books.

- ↑ Amicelle, Anthony, and David Grondin. 2021. “Algorithms as Suspecting Machines - Financial Surveillance for Security Intelligence.” In Big Data Surveillance and Security Intelligence: The Canadian Case, edited by David Lyon and David Murakami Wood. Vancouver ; Toronto: UBC Press.

- ↑ Norris, Clive, and Gary Armstrong. 2010. The Maximum Surveillance Society: The Rise of CCTV. Repr. Oxford: Berg.

- ↑ Bonelli, Laurent, and Francesco Ragazzi. ‘Low-Tech Security: Files, Notes, and Memos as Technologies of Anticipation’. Security Dialogue, vol. 45, no. 5, Oct. 2014, pp. 476–93. SAGE Journals, https://doi.org/10.1177/0967010614545200.

- ↑ Pasquinelli, Matteo. 2015. “Anomaly Detection: The Mathematization of the Abnormal in the Metadata Society.” Panel presentation presented at the Transmediale festival, Berlin, Germany.

- ↑ Canguilhem, Georges. 1978. On the Normal and the Pathological. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-009-9853-7.

- ↑ Certeau, Michel de. The Practice of Everyday Life. 1984. Translated by Steven Rendall, 1. paperback pr., 8. [Repr.], Univ. of California Press, 1988.

- ↑ Arendt, Hannah. 1970. "On Violence". New York: Harcourt, Brace & World.

The Virtual Viewer: image aesthetic assessment and digitized museum art collections

Sami P. Itävuori

But the digital photograph of the artwork still stands as a substitute for the original haptic and context-specific object tied to a subjective experience of beauty, either through encountering the work in the gallery or being able to closely examine high-res images online through sophisticated zooming tools. The mainstreaming of text-to-image generative AI with platforms like Dall-E and Midjourney generating over 15 billion images in 2024 [3] has created both fascination and concern in museum circles. While this technology appears visually familiar, it challenges traditional concepts of artistic creation and experience, provoking widespread puzzlement and sensationalism across the Galleries, Libraries, Archives and Museums sector. [4] However, this apparent divide between AI and museums can be bridged by viewing the social and technological practices of both spheres within a borderzone where the same image is understood and treated differently rather than in opposition.This means looking at how the museum is already connected to AI production pipelines, rather than as something inherently outside of it.

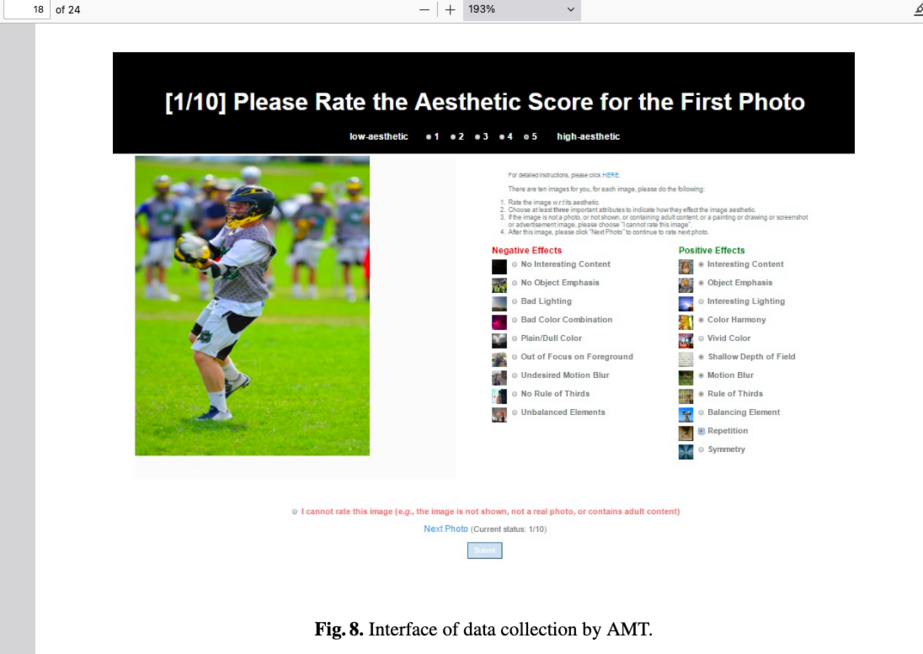

Aesthetic scoring requires Image Aesthetic Assessment (IAA) software that evaluates visual quality and aesthetic appeal of images on a scale of 0-10 (see screenshot 3). Computer scientists in IAA drawing from neurosciences, psychology, art theory or even photography manuals create quantifiable conceptions of beauty based either on qualities or the impact of this image on a viewer. These assessments can be based on a variety of formal qualities (composition, colour or lighting for example, see list of qualities used in IAA in annex 1) or trained on user-generated data from platforms like DP.Challenge or the /r/photocritique subreddit [6], where beauty emerges through statistical analysis of user preferences and feedback (Maleve and Sluis 2023, Palmer and Sluis 2024).[7][8]

Annex 1

| Authors | Year | Article | Problem | Application | Features | |

| Tang, Luo and Wang | 2011 | Content-Based Photo Quality Assessment | Image Aesthetic Assessment using feature extraction based on a set of "generally accepted" compositional rules that make a good photo | Photography | -Composition

-Lighting-Color Arranagement-Camera Setting-Topic Emphasis |

Explicit modelling on human perception but no actual sources from neurobiology, neuroaesthetics or psychology (only paper is on emotion analysis in color and the paper cited for reference on human perception regarding backgrounds is a paper on feature extraction in computer vision that does not cite neuropsychology

Human Eye extracts subjects from Background Humans respond uniformily across cultures to color (emotion analysis) |

| Data, Joshi, Li and Wang | 2006 | Studying Aesthetics in Photographic Images

Using a Computational Approach |

Feature based assessment on low level information in photographic images. Both binary scale of low to high and a regression scale from 0 to 7 | Photography | -Exposure to Light

-Colorfulness-Saturation-Hue-Rule of Thirds (composition of plane)-Familiarity-Wavelet-based Texture (grain)-Size and Aspect Ration-Region Composition-Depth of Field-Shape Convexity |

Modeling of human perception based on Rudolf Arnheim's 1951/1974 psychology book "Art and Visual Perception: A Psychology of the Creative Eye" i.e. art is the subject of fundamental cognitive processes which produce and apprehend visual culture through fundamental visual features |

| Nishiyama, Okabe, Sato and Sato | 2011 | Aesthetic Quality Classification of Photographs Based on Color Harmony | Image Aesthetic Assessment using color harmony measurements following a bag of features method | Photography | -Chroma

-Hue-RGB-Blurs-edge definition-saliency |

no mention of the human |

| Dhar, Ordonez and Berg | 2011 | High Level Describable Attributes for Predicting Aesthetics and Interestingness | Automatic image classifier assessing aesthetics for image retrieval | Photography | -Composition and Layout

-content attributes related to scene type-sky-illumination attributes |

View preference theory dervied from psychology

Palmer, E. Rosch, and P. Chase. Canonical perspective and the perception of objects. In Attention and Performance, 1981. |

| Rossano Schifanella, Miriam Redi, Luca Maria Aiello | 2015 | An Image is Worth More than a Thousand Favorites: Surfacing the Hidden Beauty of Flickr Pictures | Use Flickr likes and comments to train an automatic image selector that brings visibility to beautiful images with low popularity i.e. democratize photographic visibility on social media. Use Crowdsourcing to annotate images from 1 to 5 and provide descriptors and build large dataset (9 million) | Photography | Regressed compositional features derived from common photographic rules

-Color patterns (contrast, hue, saturation, brightness)-Spatial arrangemenent features (rule of thirds)-Textual features (overall complexity and homogeneity of an image) |

No explicit articulation of a human subject position but quotes Machajdik, J., and Hanbury, A (2010) who develop a psychological model of art perception whcih relies a lot on the Itten diagram for the association of color composition with emotional response and how this may be computed. |

| Jana Machajdik and Allan Hanbury | 2010 | Affective Image Classification using Features Inspired by

Psychology and Art Theory |

Develop a computational method that is able to extract low level and high level features to predict the emotional response of an image based on psychological and art theory | Photography and Visual Art | -Color

-textures-composition-context |

Formal elements of a pictures (such as art) have an impact on the emotional response of a human |

| Kong, S., Shen, X., Lin, Z., Mech, R., & Fowlkes, C. | 2016 | Photo aesthetic ranking network with attributes and content adaptation. | AADB participating subjects asked to provide significant features themselves using Amazon Mechanical Turk micro workers. Sample limited to 5-6 raters per image | Photography | 1. “balancing element” – whether the image contains balanced elements;

2. “content” – whether the image has good/interesting content;3. “color harmony” – whether the overall color of the image is harmonious;4. “depth of field” – whether the image has shallow depth of field;5. “lighting” – whether the image has good/interesting lighting;6. “motion blur” – whether the image has motion blur;7. “object emphasis” – whether the image emphasizes foreground objects;8. “rule of thirds” – whether the photography follows rule of thirds;9. “vivid color” – whether the photo has vivid color, not necessarily harmonious color;10. “repetition” – whether the image has repetitive patterns;11. “symmetry” – whether the photo has symmetric patterns. |

Features determined "in consultation with professional photographers" and are based on "traditional photographic principles" |

| Chen Kang, Giuseppe Valenzise, and Frédéric Dufaux. | 2020 | EVA: An Explainable Visual Aesthetics Dataset | EVA as a dataset which is crowdsourced and contains subjective attributes for aesthetics ranging from low level features (color, light etc) to semantic preferences + asks for the certainty of voter to evaluate the reliability of votes for each image | Photography | -light and colour

-composition and depth-quality, and semantics of the image |

Preferences have been handcrafted and selected based on previous studies that used simplified features for naive users (anyone non professional). The usefulness of the proposed features was then tested on crowdsourced volunteers and the relative weight of each feature weighted for different cateogories |

| Luca Marchesotti · Naila Murray · Florent Perronnin | 2014 | Discovering beautiful attributes for aesthetic image analysis | Derive high quality aesthetic features from large image text datasets which contain detailed comments about aesthetic quality of dataset. Improving on their work on AVA, the authors propose to train a new model which has first a large language model trained to extract aesthetic features from DP challenge comments on photographs. Then train an image recognition system capable of extracting features from the image (supervised learning) and judge whether it is low or high quality | Photography and by extension painting | 200 features derived from comments on DP challenge

Main attributes with success on rating images though were realted to lighting, color and composition rather than semiotic factors |

no mention of the human |

| Wenshan Wang, Su Yang, Weishan Zhang, Jiulong Zhang | 2018 | Neural Aesthetic Image Reviewer | Produce an image aesthetic rater that is also capable of producing natural language reviews to provide insight into the reasoning behind the rating. Uses DP Challenge ratings and comments as ground truths | Photography | The point is not to produce a list of features that make an image beautiful. Instead features are drawn out from the corpus of reviews that amateur users have produced "in the wild" about these images | no mention of the human beyond that we need a system that reflects how human intelligence works. i.e. by articulating "aesthetic insights" with natural language . Human intelligence sort of emerges then from the spontaneous content generated online by users |

- ↑ Virilio, Paul L'accident originel, Paris, Galilée, 2005, p. 115

- ↑ Parry, Ross. Recoding the Museum: Digital Heritage and the Technologies of Change. London: Routledge, 2007

- ↑ Everypixel Journal, People Are Creating an Average of 34 Million Images Per Day. Statistics for 2024, https://journal.everypixel.com/ai-image-statistics (accessed 30th January 2025)

- ↑ Thiel, Sonja and Bernhardt, Johannes C. ed., AI in Museums, Reflections, Perspectives and Applications. Berlin: transcript Verlag, 2023

- ↑ Schuhmann, Christoph, Romain Beaumont, Richard Vencu, Cade Gordon, Ross Wightman, Mehdi Cherti, Theo Coombes, et al. "LAION-5B: An Open Large-Scale Dataset for Training Next Generation Image-Text Models." in 36th Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS 2022), Track on Datasets and Benchmarks, arXiv, 2022.

- ↑ Vera Nieto, Daniel, Luigi Celona, and Clara Fernandez-Labrador. "Understanding Aesthetics with Language: A Photo Critique Dataset for Aesthetic Assessment." In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision, 2023.

- ↑ Maleve, Nicolas, and Katrina Sluis. "The Photographic Pipeline of Machine Vision; or, Machine Vision's Latent Photographic Theory." Critical AI (2023).

- ↑ Palmer, D., & Sluis, K.. The Automation of Style: Seeing Photographically in Generative AI . Media Theory, 8(1), 159–184. 2024 Retrieved from https://journalcontent.mediatheoryjournal.org/index.php/mt/article/view/1072

- ↑ Wasielewski, Amanda. Computational Formalism: Art History and Machine Learning. MA: MIT Press, 2023your reference

- ↑ Balshaw, Maria, Gathering of Strangers: Why Museums Matter, London: Tate Publishing, 2024

Annex 1 References

Datta, Ritendra, Dhiraj Joshi, Jia Li, and James Z. Wang. "Studying Aesthetics in Photographic Images Using a Computational Approach." In Computer Vision – ECCV 2006: 9th European Conference on Computer Vision, 288-301. Graz, Austria: Springer, 2006.

Dhar, Sagnik, Vicente Ordonez, and Tamara L. Berg. "High Level Describable Attributes for Predicting Aesthetics and Interestingness." In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 1657-1664. Providence, RI: IEEE, 2011.

Kong, Kuang-Yu, Gao, Yang, Xu, Timothy M., and Jing, Xuan. "Understanding Aesthetics with Language: A Photo Critique Dataset for Aesthetic Assessment." IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (2022): 2984-2993.

Li, Congcong, Guangyao Zhai, and Tianyu Liu. "Aesthetic Assessment of Paintings Based on Visual Balance." IEEE Transactions on Multimedia 21, no. 10 (2019): 2475-2487.

Marchesotti, Luca, Florent Perronnin, and Nicu Sebe. "Will the Machine Like Your Image? Automatic Assessment of Beauty in Images with Machine Learning Techniques." Paper presented at the First International Workshop on Social Signal Processing, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2009.

Nishiyama, Masashi, Takahiro Okabe, Imari Sato, and Yoichi Sato. "Aesthetic Quality Classification of Photographs Based on Color Harmony." In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 33-40. Providence, RI: IEEE, 2011.

Park, Tae-Suh, and Byoung-Tak Zhang. "Consensus Analysis and Modeling of Visual Aesthetic Perception." IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics: Systems 49, no. 8 (2019): 1626-1636.

Tang, Xiaoou, Wei Luo, and Xiaokang Wang. "Content-Based Photo Quality Assessment." IEEE Transactions on Multimedia 13, no. 4 (2011): 589-602.