GPU

The king of Denmark, Jensen Huang (CEO and founder of Nvidia), and Nadia Carlsten (CEO of the Danish Center for AI Innovation) pose for a photo holding an oversized cable in front of a bright screen full of sparkles. It is the inauguration of Denmark's "sovereign" AI supercomputer, aka Gefjon, named after the Nordic goddess of ploughing.

"Gefion is going to be a factory of intelligence. This is a new industry that never existed before. It sits on top of the IT industry. We’re inventing something fundamentally new" (https://blogs.nvidia.com/blog/denmark-sovereign-ai-supercomputer/)

Gefion is powered by 1,528 H100's, a GPU developed by Nvidia. This object, the Graphics Processing Unit, is a key element that, arguably, paves the way for Denmark's sovereignty and heavy ploughing in the AI world. Beyond all the sparkles, this photo shows the importance of the GPU object not only as a technical matter, but also a political and powerful element of today's landscape.

Since the boom of Large Language Models, Nvidia's graphic cards and GPUs have become somewhat familiar and mainstream. The GPU powerhouse, however, has a long history that predates their central position in generative AI, including the stable diffusion ecosystem: casual and professional gaming, cryptocurrencies mining, and just the right processing for n-dimensional matrices that translate pixels and words into latent space and viceversa.

What is a GPU?

A graphics processing unit (GPU) is an electronic circuit focused on processing images in computer graphics. Originally designed for early videogames, like arcades, this specialised hardware performs calculations for generating graphics in 2D and later for 3D. While most computational systems have a Central Processing Unit (CPU), the generation of images, for example, 3D polygons, requires a different set of mathematical calculations. GPUs gather instructions for video processing, light, 3D objects, textures, etc. The range of GPUs is vast, from small and cheap processors integrated into phones and smaller devices, to state of the art graphic cards piled in data centres to calculate massive language models.

What is the network that sustains this object?

From the earth to the latent space

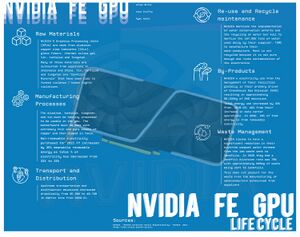

Like many other circuits, GPUs require a very advance production process, that starts with mineral mining for both common and rare minerals (silicon, gold, hafnium, tantalum, palladium, copper, boron, cobalt, tungsten, etc). Their life-cycle and supply chain locate GPUs into a material network with the same issues of other chips and circuits: conflict minerals, labour rights, by-products of manufacturing and distribution, and waste. When training or generating AI responses, the GPU is the object that consumes the most energy in relation to other computational components. A home-user commercially available GPU like the GeForce RTX 5090 can consume 575 watts, almost double than a CPU in the same category. Industry GPUs like the A100 use a similar amount of energy, with the caveat that they are usually managed in massive data centres. Allegedly, the training of GPT4 used 25,000 of the latter, for around 100 days (i.e. approximately 1 gigawatt, or 100 million led bulbs). This places GPUs in a highly material network that is for the most part invisible, yet enacted with every prompt, LoRA training, and generation request.

Perhaps the most important part of the GPU in our Objects of interest and necessity network and maps, is that this object is a, if not the, translation piece: most of the calculations to and from "human-readable" objects, like a painting, a photograph or a piece of text, into an n-number of matrices, vectors, and coordinates, or latent space, are made possible by the GPU. In many ways, the GPU is a transition object, a door into and out of a, sometimes grey-boxed, space.

The GPU cultural landscape and its recursive publics

It is also a mundane object, historically used by gamers, thus owning much of its history and design to the gaming culture. Indeed, the development of computer games demand fuelled the design and development of the current GPU capabilities. In own our study, we use an Nvidia RTX 3060ti super, bought originally for gaming purposes. When talking about current generative AI, populated by major tech players and trillion-valued companies and corporations, we want to stress the overlapping history of digital cultures, like gaming and gamers, that shape this object.

Being a material and mundane object also allows for paths towards autonomy. While our GPU was originally used for gaming, it opened a door for detaching from big tech industry players. With some tuning and self-managed software, GPUs can process queries on open, mid-size and large, language models, including stable diffusion. That is, we can generate our own images, or train LoRA's, without depending on chatgpt, copilot, or similar offers. Indeed, plenty of enthusiast follow this path, running, tweaking, branching, and reimagining open source models thanks to GPUs. CivitAI is a great example of a growing universe of models, with different implementations of autonomy: from niche communities of visual culture working on representation, communities actively developing prohibited, censored, fetishised, and specifically pornographic images. CivitAI hosts alternative models for image generation responding to specific cultural needs, like a specific manga style or anime character, greatly detached from the interests of Silicon Valley's AI blueprints or nation's AI sovereignty imaginaries.

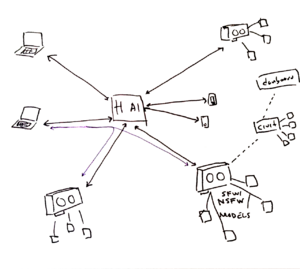

A horde of graphic cards

The means of production of these communities, alongside with collaboratively labelled data, is the GPU. AI Horde, for example, is a distributed cluster of "workers", i.e. GPUs, that uses open models, including many community-generated ones from CivitAI. The "volunteer crowd-sourced" project acts as a hub that directs image generation requests from different interfaces (e.g. Artbot, Mastodon, etc) towards individual GPU workers in the network. As part of our project, our GPU is (sometimes) connected to this network, offering image generation (using selected models) to any request from the interfaces (Websites, apis, etc).

"Why should I use the Horde instead of a free service?

Because when the service is free, you're the product! Other services running on centralized servers have costs—someone has to pay for electricity and infrastructure. The AI Horde is transparent about how these costs are crowdsourced, and there is no need for us to change our model in the future. Other free services are often vague about how they use your data or explicitly state that your data is the product. Such services may eventually monetize through ads or data brokering. If you're comfortable with that, feel free to use them. Finally, many of these services do not provide free REST APIs. If you need to integrate with them, you must use a browser interface to see the ads"(https://aihorde.net/faq).

Projects like this one show that there is an explicit interest in alternatives to the mainstream generative AI landscape, based on collaboration strategies rather than a surveillance/monetisation model, also known as "surveillance capitalism,[1] an extractive model that has become the economic standard of many digital technologies (in many cases with the full support of democratic institutions). In this sense, Horde AI is a project that deviates towards a form of technical collaboration, producing its own models of exchange in the form of kudos currency, which behaves a bit more of a barter system, where the main material is GPU processing power.

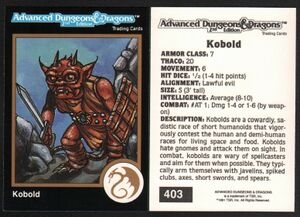

But perhaps more importantly, CivitAI, Horde AI, and other objects of interest, not only show the necessity and the role of alternative actors and processes in the AI ecosystem, but also the importance of the cultural upbringings of the more wild AI landscape. In a similar fashion to the manga and anime background of the CivitAI population, AI horde is a project that evolved from groups interested in role-playing. The name horde reflects this imprinting, and the protocol comes from a previous project named "KoboldAI", in reference to the Kobold monster from the role-playin game Advanced Dungeons & Dragons. The material infrastructure of the GPU overlaps with a plethora of cultural layers, all with their own politics of value, collaboration, and ethics, influencing alternative imaginaries of autonomy. And much of the aspects of the recursive publics in this landscape are technically operationalized through the GPU object.

How does it evolve through time?

Jacob Gaboury[2] follows 30 years of computational research geared towards producing the GPU (MORE ON THIS) -- emphasis on parallel computing, and hyperspecialized work "detached" from CPU computation.

- gaming

- crypto

The creation of cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin

- neural networks computation

- llm's

- large scale industrial AI

Do Graphics Processing Units Have Politics? https://cargocollective.com/gansky/Do-Graphics-Processing-Units-Have-Politics

How does it create value? Or decrease / affect value?

- buzz, horde, cryptocurrencies

- covid19 scarcity

- production value (e.g. civitAI)

- national AI sovereignty

- autonomy

- military?

What is its place/role in techno cultural strategies?

How does it relate to autonomous infrastructure?

- ↑ Zuboff, S. (2022). Surveillance Capitalism or Democracy? The Death Match of Institutional Orders and the Politics of Knowledge in Our Information Civilization. Organization Theory, 3(3), 26317877221129290. https://doi.org/10.1177/26317877221129290

- ↑ Gaboury, J. (2021). Image Objects: An Archaeology of Computer Graphics. The MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/11077.001.0001