Objects of interest and necessity: Difference between revisions

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

''During my eight years of going to the Keskins’ for supper, I was able to squirrel away 4,213 of Füsun’s cigarette butts. Each one of these had touched her rosy lips and entered her mouth, some even touching her tongue and becoming moist, as I would discover when I put my finger on the filter soon after she had stubbed the cigarette out.The stubs, reddened by her lovely lipstick, bore the unique impress of her lips at some moment whose memory was laden with anguish or bliss, making these stubs artifacts of a singular intimacy'' (excerpt from Chapter 68) | ''During my eight years of going to the Keskins’ for supper, I was able to squirrel away 4,213 of Füsun’s cigarette butts. Each one of these had touched her rosy lips and entered her mouth, some even touching her tongue and becoming moist, as I would discover when I put my finger on the filter soon after she had stubbed the cigarette out.The stubs, reddened by her lovely lipstick, bore the unique impress of her lips at some moment whose memory was laden with anguish or bliss, making these stubs artifacts of a singular intimacy'' (excerpt from Chapter 68) | ||

The collection of objects are the things that makes the story, and also what makes the story real. Objects contain an associative power, that literally creates memories (the young Marcel in Proust’s In Search of Lost Times (À la recherche du temps perdu) who eats a cake to create a novel, is perhaps the most famous literary example of this). Therefore, this catalogue is not just a collection of the objects that makes generative AI images, but also an exploration of an imaginary of AI image creation through the collection and exhibition objects – and in particular, an imaginary of ‘autonomy’. | The collection of objects are the things that makes the story, and also what makes the story real. Objects contain an associative power, that literally creates memories (the young Marcel in Proust’s ''In Search of Lost Times'' (''À la recherche du temps perdu'') who eats a madeleine cake to create a novel, is perhaps the most famous literary example of this). Therefore, this catalogue is not just a collection of the objects that makes generative AI images, but also an exploration of an imaginary of AI image creation through the collection and exhibition of objects – and in particular, an imaginary of ‘autonomy’. | ||

Most people’s experiences with generative AI image creation come from platforms like OpenAI’s DALL-E, Google’s Gemini, or other services. There is a whole ecology of services that are distinct yet often based on the same underlying models or techniques of so-called ‘diffusion’. Nevertheless, there are also communities who for different reasons seek some kind of independence and autonomy from the mainstream platforms. It may be that they are unsatisfied with the stylistic outputs; say, interested in not just manga style images, but a particular manga style (the English language image board or gallery | Most people’s experiences with generative AI image creation come from platforms like OpenAI’s DALL-E, Google’s Gemini, or other services. There is a whole ecology of services that are distinct yet often based on the same underlying models or techniques of so-called ‘diffusion’. Nevertheless, there are also communities who for different reasons seek some kind of independence and autonomy from the mainstream platforms. It may be that they are unsatisfied with the stylistic outputs; say, interested in not just manga style images, but a particular manga style (the English language image board or gallery [https://danbooru.donmai.us Danbooru] is an example of this, where much content is erotic). Others may have issues with the platform model itself, and how it compromises ideals of free/’libre’ and open-source software (aka F/LOSS). They want image generation to be more broadly available, free of costs, use less processing power, or open it up for new technical ideas and experimentation. For instance, OpenAI is not so open as the name indicates, but has a complicated history where commercialization, partnerships and dependencies of other tech corporations (like Microsoft) have become increasingly central for its operations. The objects presented in this catalogue all refer to autonomous practices of AI image generation. That is, rather than explaining how generative AI works ([https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-32236-6_51 as many researchers and critics of AI call for]), our interest lies in opening up for an understanding of what it takes to make AI image generation work, and also to make it work separately from mainstream platforms and capital interests. | ||

Our outset is ‘Stable Diffusion’, a generative AI model that produces images from text prompts. Characteristically, the company behind ([https://stability.ai Stability AI]) uses the same ‘diffusion’ technology as many of the commercial services, but with heavily reduced labour costs in producing the data set behind, and the description of the images necessary to train the model. Explained a bit technically, Christoph Shuman, an independent high school teacher, found a way to ‘scrape’ the internet for links to images with alt text (text that describes images for people with disabilities) and filter out the non-sensical text (using [[CLIP]]), thereby providing a fully annotated data set ([[LAION]]) for only 5,000 USD. On this background, Stable Diffision has been released under a [https://stability.ai/license community license] that allows for research, non-commercial, and also limited commercial use. That is, users can freely install and use Stable Diffusion under conditions similar to much other F/LOSS software. | Our outset is ‘Stable Diffusion’, a generative AI model that produces images from text prompts. Characteristically, the company behind ([https://stability.ai Stability AI]) uses the same ‘diffusion’ technology as many of the commercial services, but with heavily reduced labour costs in producing the data set behind, and the description of the images necessary to train the model. Explained a bit technically, Christoph Shuman, an independent high school teacher, found a way to ‘scrape’ the internet for links to images with alt text (text that describes images for people with disabilities) and filter out the non-sensical text (using [[CLIP]]), thereby providing a fully annotated data set ([[LAION]]) for only 5,000 USD. On this background, Stable Diffision has been released under a [https://stability.ai/license community license] that allows for research, non-commercial, and also limited commercial use. That is, users can freely install and use Stable Diffusion under conditions similar to much other F/LOSS software. | ||

Subesequently there is range of other F/LOSS software that enables user interfaces to Stable Diffusion and also a lively visual culture who uses and also builds on Stable Diffusion models. This includes, for instance, [https://civitai.com CivitAI] that allows users to share and download AI models and also for its community of users to both use its servers for a [[Currencies|virtual token]] (called buzz) and also show and sell their AI-generated images. [https://www.deviantart.com DevianArt] is another platform that functions in similar ways. Or, [https://huggingface.co Hugging Face], which functions like a repository of user-created AI models that can be used in other F/LOSS applications (such as [https://drawthings.ai Draw Things]) to generate images or ‘tweak’ the models, using so-called [[LoRA|LoRAs]]. Many of these sites linger on the edge of capital interests and are often both communities of practice in one way or the other interested in autonomy and corporations geared towards maximizing value extraction. However, one also finds [https://stablehorde.net Stable Horde], that in a peer-to-peer fashion allows its community to access each other’s machines for processual power – contrary to conventional AI platforms where one depends on a corporate service. In other words, what autonomy is, and what it means to separate from capital interests is by no means uniform – the range of agents, dependencies, flows of capital, and so on, can be difficult to comprehend and is in constant flux. This, we have tried to capture in our description of the objects, guided by a set of questions: | Subesequently there is range of other F/LOSS software that enables user interfaces to Stable Diffusion and also a lively visual culture who uses and also builds on Stable Diffusion models. This includes, for instance, [https://civitai.com CivitAI] that allows users to share and download AI models and also for its community of users to both use its servers for a [[Currencies|virtual token]] (called buzz) and also show and sell their AI-generated images. [https://www.deviantart.com DevianArt] is another platform that functions in similar ways. Or, [https://huggingface.co Hugging Face], which functions like a repository of user-created AI models that can be used in other F/LOSS applications (such as [https://drawthings.ai Draw Things]) to generate images or ‘tweak’ the models, using so-called [[LoRA|LoRAs]]. Many of these sites linger on the edge of capital interests and are often both communities of practice in one way or the other interested in autonomy ''and'' corporations geared towards maximizing value extraction. However, one also finds [https://stablehorde.net Stable Horde], that in a peer-to-peer fashion allows its community to access each other’s machines for processual power – contrary to conventional AI platforms where one depends on a corporate service. | ||

In other words, what autonomy is, and what it means to separate from capital interests is by no means uniform – the range of agents, dependencies, flows of capital, and so on, can be difficult to comprehend and is in constant flux. This, we have tried to capture in our description of the objects, guided by a set of questions: | |||

# What is the network that sustains this object? | # What is the network that sustains this object? | ||

# How does it evolve through time? | # How does it evolve through time? | ||

Revision as of 15:00, 3 June 2025

What is an Object of Interest/Necessity?

With the notion of an ‘object of interest’ a guided tour of a place, a museum or collection likely comes to mind. One may easily read this compilation of texts as a catalogue for such a tour in a social and technical system, where we stop and wonder about the different objects that, in one way or the other, take part in the generation of images by artificial intelligence (AI).

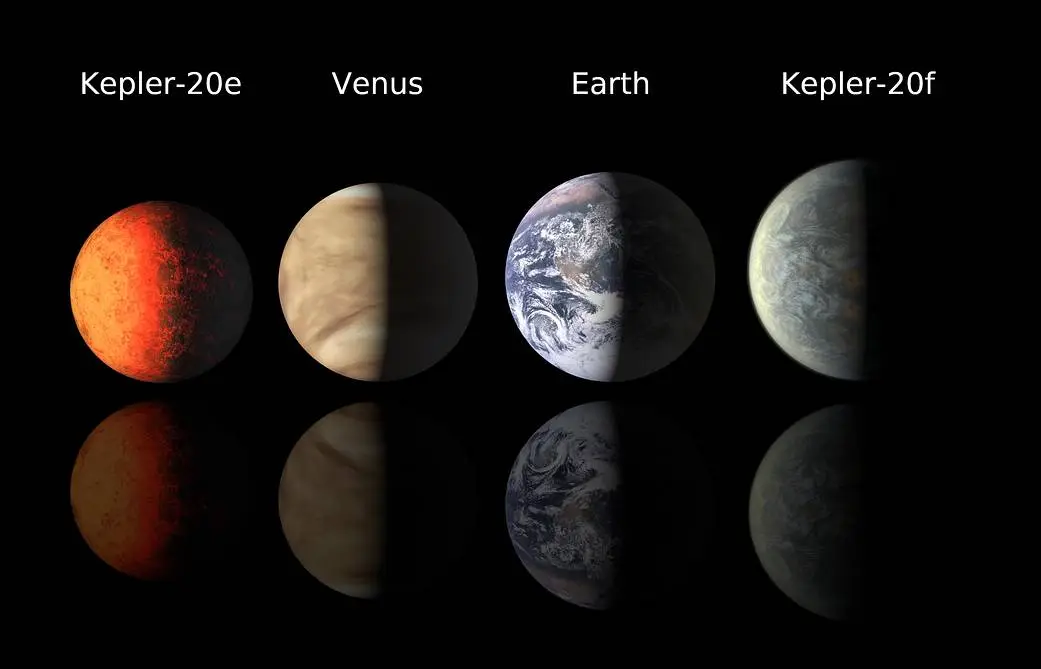

In science an object of interest sometimes refers to what one might call the potentiality of an object. Take for instance, the famous Kepler telescope whose mission was to search the Milky Way for exoplanets (planets outside our own solar system). Among all the stars, there are candidates for this, or so-called Kepler Objects of Interest (KOI) that are documented, indexed and catalogued. In similar ways, this catalogue is the outcome of an investigative process where we – by trying out different software, reading documentation and research, looking into communities of practice that experiment with AI image creation, and more – have sought to understand the things that make generative AI images possible; that is, the underlying dependencies on relations between communities, models, technical units, and more in AI image creation. Within this system there is not just a functional apparatus, but also an ‘imaginary’; that is, there are underlying expectations and norms (for planetary existence) that are met in specific objects.

The catalogue, however, is strictly speaking not scientific, and should not be taken too serious as such. It is not as if there are a set of defined parameters by which we have prioritized some objects over others. One can also think of an object of interest in a different way; as something that is not just the manifestation of an imaginary, but also what produces it. Take for instance Orhan Pamuk’s famous Museum of Innocence. It is a book by the Nobel Prize winning author, but also an entry ticket to a really existing museum in Istanbul, where one can find, amongst other items, a showcase of 4,213 cigarette butts, smoked by Füsun, the object of Kemal, the main character’s love.

During my eight years of going to the Keskins’ for supper, I was able to squirrel away 4,213 of Füsun’s cigarette butts. Each one of these had touched her rosy lips and entered her mouth, some even touching her tongue and becoming moist, as I would discover when I put my finger on the filter soon after she had stubbed the cigarette out.The stubs, reddened by her lovely lipstick, bore the unique impress of her lips at some moment whose memory was laden with anguish or bliss, making these stubs artifacts of a singular intimacy (excerpt from Chapter 68)

The collection of objects are the things that makes the story, and also what makes the story real. Objects contain an associative power, that literally creates memories (the young Marcel in Proust’s In Search of Lost Times (À la recherche du temps perdu) who eats a madeleine cake to create a novel, is perhaps the most famous literary example of this). Therefore, this catalogue is not just a collection of the objects that makes generative AI images, but also an exploration of an imaginary of AI image creation through the collection and exhibition of objects – and in particular, an imaginary of ‘autonomy’.

Most people’s experiences with generative AI image creation come from platforms like OpenAI’s DALL-E, Google’s Gemini, or other services. There is a whole ecology of services that are distinct yet often based on the same underlying models or techniques of so-called ‘diffusion’. Nevertheless, there are also communities who for different reasons seek some kind of independence and autonomy from the mainstream platforms. It may be that they are unsatisfied with the stylistic outputs; say, interested in not just manga style images, but a particular manga style (the English language image board or gallery Danbooru is an example of this, where much content is erotic). Others may have issues with the platform model itself, and how it compromises ideals of free/’libre’ and open-source software (aka F/LOSS). They want image generation to be more broadly available, free of costs, use less processing power, or open it up for new technical ideas and experimentation. For instance, OpenAI is not so open as the name indicates, but has a complicated history where commercialization, partnerships and dependencies of other tech corporations (like Microsoft) have become increasingly central for its operations. The objects presented in this catalogue all refer to autonomous practices of AI image generation. That is, rather than explaining how generative AI works (as many researchers and critics of AI call for), our interest lies in opening up for an understanding of what it takes to make AI image generation work, and also to make it work separately from mainstream platforms and capital interests.

Our outset is ‘Stable Diffusion’, a generative AI model that produces images from text prompts. Characteristically, the company behind (Stability AI) uses the same ‘diffusion’ technology as many of the commercial services, but with heavily reduced labour costs in producing the data set behind, and the description of the images necessary to train the model. Explained a bit technically, Christoph Shuman, an independent high school teacher, found a way to ‘scrape’ the internet for links to images with alt text (text that describes images for people with disabilities) and filter out the non-sensical text (using CLIP), thereby providing a fully annotated data set (LAION) for only 5,000 USD. On this background, Stable Diffision has been released under a community license that allows for research, non-commercial, and also limited commercial use. That is, users can freely install and use Stable Diffusion under conditions similar to much other F/LOSS software.

Subesequently there is range of other F/LOSS software that enables user interfaces to Stable Diffusion and also a lively visual culture who uses and also builds on Stable Diffusion models. This includes, for instance, CivitAI that allows users to share and download AI models and also for its community of users to both use its servers for a virtual token (called buzz) and also show and sell their AI-generated images. DevianArt is another platform that functions in similar ways. Or, Hugging Face, which functions like a repository of user-created AI models that can be used in other F/LOSS applications (such as Draw Things) to generate images or ‘tweak’ the models, using so-called LoRAs. Many of these sites linger on the edge of capital interests and are often both communities of practice in one way or the other interested in autonomy and corporations geared towards maximizing value extraction. However, one also finds Stable Horde, that in a peer-to-peer fashion allows its community to access each other’s machines for processual power – contrary to conventional AI platforms where one depends on a corporate service.

In other words, what autonomy is, and what it means to separate from capital interests is by no means uniform – the range of agents, dependencies, flows of capital, and so on, can be difficult to comprehend and is in constant flux. This, we have tried to capture in our description of the objects, guided by a set of questions:

- What is the network that sustains this object?

- How does it evolve through time?

- How does it create value? Or decrease / affect value?

- What is its place/role in techno cultural strategies?

- How does it relate to autonomous infrastructure?

The murkiness of autonomous AI image generation implicates our interests in the objects, too. Therefore, the objects are not just of 'interest', but also of ‘necessity’. The Cuban artist and designer, Ernesto Oroza speaks of “objects that are at the same time an understanding of a need and the answer to it.” (Oroza) Oroza speaks of, for instance, the Cuban phenomenon S-net, short for Street network, a form of wireless network that is community driven, but occurs in a situation where people want to play online games or access the internet for other reasons, but where internet access is limited and regulated by the government. S-net is autonomous and independent, and yet, in order to exist, it also accepts the official demands of, for instance, not discussing politics online.

If one asks what qualifies as autonomy in AI image generation, and the intent is to catalogue what autonomous AI image generation is and consists of, we answer by showcasing what it looks like, by necessity – because it always exists in relation to a fluctuation set of correspondences, conditions and dependencies. In much the same way: the catalogue of ‘Kepler Objects of Interest’ might reflect the potential of objects to be something, but what something is always also looks like something; like love that might look like 4,213 cigarette butts exhibited in the Museum of Innocence. In this sense, the catalogue is also always in flux, and with its unfinished nature, we also invite others to continue its edition.

Notes from meeting 10/02/2025

Objects of interest / e.g. objects that could be represented at an exhibition.

Object of necessity / Ernesto Oroza (https://www.ernestooroza.com/category/objects-of-necessity-projects/) - also transaction models, refers to conditions of production and values

... see also: https://temporaryservices.org/served/projects-by-name/prisoners-inventions/ (Brett Bloom), https://artistsbookreviews.com/2024/04/22/prisoners-inventions/, https://halfletterpress.com/prisoners-inventions-new-edition-pdf/

For reference, the questions are:

- What cultural and technical strategies can foster democratic, socially and environmentally sustainable knowledge infrastructures?

- How do these strategies facilitate collective examination of tensions inherent in the technologies themselves?

- How can social collectives, connecting academia and grassroots movements, foster the creation of autonomous services and infrastructures that enhance knowledge, participation, and political immediacy?

1. Taking each object of interest, we have to demonstrate how cultural and technical strategies are embedded in it and how they relate to infrastructure of participation. This can be done by mapping/diagramming the network of attachments of the object

2. In a second stage, examine the controversies and tensions surrounding these objects. Here focus on licenses, intellectual property is a rich starting point (see Open Infrastructures article)

3. Emphasize the dimension of knowledge production and sharing in these environments + connect to the practices of workshops during the whole project

Questions to be answered

What is the network that sustains this object?

- How does it move from person to person, person to software, to platform, what things are attached to it (visual culture)

- Networks of attachments

- How does it relate / sustain a collective? (human + non-human)

How does it evolve through time?

Evolution of the interface for these objects. Early chatgpt offered two parameters through the API: prompt and temperature. Today extremely complex object with all kinds of components and parameters. Visually what is the difference? Richness of the interface in decentralization (the more options, the better...)

How does it create value? Or decrease / affect value?

What is its place/role in techno cultural strategies?

How does it relate to autonomous infrastructure?

Candidates

- GPU: NVIDIA card

- Fine tuning: LoRA

- Semantics: Negative prompt, Taxonomies

- Currencies: Point, Buzz, Kudos

- Standards, transparency, protocol: Model card

- Configs

- Maps

Maybe on shorter versions (Than the ones above):

- dataset

- clip

- prompt

- vae

Images